Some might have questioned Kurk Shriver’s sanity when he signed up to instruct linemen along the outskirts of a dense jungle in the Republic of Suriname. Shriver, a lineman on the BPA barehand crew, already spends roughly 200 days a year traveling throughout the Northwest. The 12,000-mile roundtrip to Suriname would mean an additional three weeks away from his wife and consume his paid vacation. Plus, there was the threat of venomous snakes, swarms of disease-carrying mosquitos and the stress of taking rounds of pills to prevent malaria, as well as the sting of hepatitis and yellow fever inoculations. Not to mention the challenge of conducting electrical training while negotiating a language barrier.

But when Shriver was asked to join a group of Northwest linemen on a mission last October to teach transmission, distribution and safety to South American utility workers, this seasoned lineman says “no” would have been the crazy answer.

“If I have knowledge that can help someone be a father or husband another day because they didn’t get hurt or killed at work, then it is worth it for me to help,” says Shriver. “It’s worth it to both my wife and me.”

The idea for the course came from former BPA foreman III Brady Hansen, who now works at Avista Utilities in Spokane, Washington. Hansen was working at Avista’s lineman school when a group of electrical engineers from Suriname toured the facility. Hansen learned that the safety protocols and equipment that are so common in the United States are nearly nonexistent in the small South American country.

Hansen recruited Shriver as well as Rick Irvine, a retired foreman from Avista and a current instructor at the lineman school, and Joe Baker, a lineman from Douglas County PUD in Washington. They organized a Train-the-Trainers session at the government utility Energiebedrijven Suriname (EBS) in the nation’s capital of Paramaribo.

A Country in the Dark

Much of Suriname is isolated, with the Atlantic Ocean to its north and the vast jungles of Brazil to its south. The country shares its western and eastern borders with Guyana and French Guiana. Suriname has one of the most diverse ethnic backgrounds in the world, which can be traced back to the mid-1600s when the Dutch and British first arrived to the area seeking sugar and gold.

The country’s urban areas were energized in the early 1900s. But after the country’s independence from the Dutch in the 1970s, a civil war broke out in the 1980s. Since then, there have been limited funds for expansion to remote areas and improvements to existing infrastructure. Suriname has struggled to keep pace with countries such as the United States.

According to Shriver, when electrification came to the United States, line work became one of the most dangerous jobs in the nation. Although no statistics were documented in the late 1800s, many linemen believe the death toll — mostly due to electrocution — was as high as one in two workers. Employees’ labor concerns resulted in the formation of a union to promote reasonable methods of work.

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the efforts of employers, safety and health professionals, unions and advocates have had a dramatic effect on workplace safety. OSHA records show in the last four decades, workplace fatalities have been reduced by more than 65% and occupational injury and illness rates have declined by 67%. Surinamese linemen, however, haven’t had the support and protections of an organized union.

“They’ve been working with electricity for a long time, but it reminded me of what it must have been like 80 years ago in the U.S., when guys were getting hurt but the men didn’t know why,” says Shriver. “I could look at these men and see burns and scars from their accidents. Some of them knew why they got hurt and some didn’t.”

Building a Training Yard

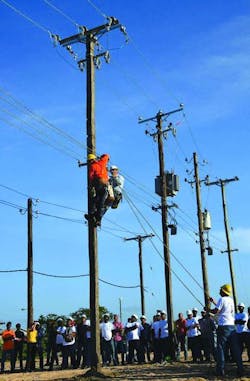

On the day Shriver and crew arrived in Paramaribo, they were taken to a bare lot. The Surinamese didn’t have a training ground but were inspired to build one. Shriver jumped in to help, marking where the poles should be installed.

A couple days later, the utility had its first pole-climbing yard with a simulated 161-kV line. Some poles were made of wood, cut by axe, and some were made of steel, both of which are common in South America.

But before they put the yard to use, they spent a few days of training in the classroom, covering basic lineman skills and electrical theory. Shriver says it gave him and his fellow trainers a chance to earn the respect of the local linemen while assessing the peaks and valleys of their knowledge.

According to Shriver, the Surinamese linemen were hard workers and extremely eager to be a part of the training. “They all wanted to learn more to protect themselves and their coworkers.”

Historically, Suriname line maintenance has been done from ladders leaning against poles or from bucket trucks.

“Many men have been hurt from working on ladders,” says Shriver. “The added leverage of the ladder leaning against the top of a damaged pole can cause it to fall to the ground, along with the worker.”

Shriver and fellow trainers packed with them standard North American wood pole climbing gear and fall protection items.

“They were donated by IBEW members, contractors and North American businesses sympathetic to the plight of the Suriname linemen,” says Shriver. “In the past, as fall protection requirements have changed, people would destroy the outdated gear. Both individuals and businesses now recognize that you can save a life by getting these items to people who have no protection at all.”

The show-and-tell served as an opportunity for utility workers to see gear and methods that may serve as low-cost safe alternatives to an unsteady ladder or in areas a bucket truck can’t access.

Suriname Energized

The crews in Suriname work on de-energized lines, causing regular unplanned outages for Paramaribo residents. However, de-energizing a power line does not mean it is free of electrical hazards; the risk of electrocution still exists.

“Also, planned intermittent outages happen regularly to limit electricity usage during the peak seasons of capacity,” Shriver adds. “This is a deterrent to new businesses and people coming in, because it’s viewed as an unreliable power source.”

Only once has a lineman climbed a steel lattice tower on a 161-kV transmission line — the utility’s highest voltage line — since it was raised more than three decades ago. Now, the transmission line is in dire need of attention.

As an introduction to 161-kV line maintenance, Shriver and the other trainers showed the local linemen how to replace insulators on the top position of the double-circuit tower. Shriver says they now have what they need to inspect towers for loose steel. They can also assess the condition of the towers and the hardware, and identify inadequate or missing parts.

Shriver says over multiple years, EBS workers will continue to receive training from U.S. linemen volunteers. The next session is scheduled for fall 2015 and will likely cover how to safely rig towers for dead-end tension. It will also cover splicing and adding new conductor. EBS also plans to add a steel lattice tower to the training yard.

Teaching Safe Grounding Methods

To demonstrate electrical grounding methods, the U.S. instruction crew hauled a dirt box training tool from Harvey Haven — BPA’s patron saint of safety — down to South America.

“One lineman thought the line was safe to work on and didn’t understand why his coworker received a shock and fell from the pole,” says Shriver. “When we showed him the dirt box, he said he finally understood what was wrong. Now, he can protect his co-workers to make sure they’re never in that situation again.”

The pine box is 3-ft long by 2-ft wide and deep. It’s filled with dirt and two wood-dowel “towers,” connected with copper wire and grounded (to protect a worker from accidental exposure to high voltages). A light bulb, representing a lineman at work, sits along the wire between the towers. When connected to a power source, the bulb glows, proving that electricity can complete an electrical circuit through the lineman’s body, in spite of the supposed protection of the grounding.

“Nothing pleases me more than knowing that Kurk and the team used a dirt box as part of their training program,” says Haven, who has shared the training tool with more than 45 organizations in North America. “After he got back, he called me to tell me how things went. He made my day when he told me that now there were dirt boxes on two continents saving lives.”

Haven, who was inducted into the International Lineman Hall of Fame on May 16 for his work in educating linemen in safe work practices, says he was proud to learn of Shriver’s

efforts to help fellow utility workers.

“It is extremely important that linemen like Kurk and Brady, another very impressive person, take the initiative to train outside of BPA,” says Haven. “People like them are out there making a difference in the safety and quality of workmanship in the line trade. We couldn’t exist if it weren’t for people like them.”

Shifting the Safety Culture

When recalling his experience, Shriver says what impressed him the most about his trip was the effort and determination of the government utility to improve its transmission and distribution maintenance program.

“Of all the places I’ve been in the U.S., I’ve never seen a company work so hard to improve their safety and skills,” says Shriver. “They could be a model for us in many ways, even the way everyone works together to improve what they have, from the CEO down to the parts boy, the lowest guy in the crew.”

More than 100 people completed the Suriname-American training. “We changed the safety culture in Suriname in a few weeks,” Shriver says. “They now have safety job briefings each day before they start work; they know the importance of personal protective equipment; and they hold safety meetings. They also know and practice pole top and bucket rescue; can calculate the weight and tension on conductor and work in a safer environment.”

Shriver continues to share his experiences around the U.S. to recruit new trainers and looks forward to returning to Suriname this fall.

Julie Paynter ([email protected]) is a public affairs specialist at the Bonneville Power Administration and supports employee communications for the agency’s continuity of operations, fall protection, safety and security departments.