Renee Nickles may have worked in the line trade for three decades, but she has seen few other women embrace the adventure of working as a lineman. With skilled labor shortages and opportunities nationwide, however, now is the time for more women to consider line work.

“As many companies seek to diversify the workplace, it’s a great time for women to enter the trade,” said Nickles, the field operations supervisor for Portland General Electric (PGE). “The line trade is open to women if they want to go into that direction. If women put in the time, are physically fit enough to do the work and have mental stamina, the sky is the limit.”

To make it in the trade, women must be mentally strong to weather the ups and downs, not be afraid of heights, be teachable and love the outdoors.

“Some days are overwhelmingly difficult, but you must be willing to stay the course,” Nickles said. “At the end of the day, you feel good and have a smile on your face. You can perform tasks most people would never even consider doing in these types of conditions. Linemen are a different breed of people. We go out in the night and storms under the most adverse conditions. It’s not for everyone.”

Back in 1978, Rosa Vasquez, who was recently inducted into the National Lineman Hall of Fame, was recognized as the first female American lineman. Fast forward to today, and about 4.1 percent or 137 of electric power line installers and repairers are women in the United States, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In Canada, women in the electricity sector’s trade and technical roles represent 6 percent of the workforce, and women as Powerline Technicians represent 1 percent to 2 percent of the workforce. This means between 76 to 153 women are powerline technicians in Canada, said Lana Norton, founder and executive director of the Women of Power Line Technicians (Women of PLT).

“Challenges in the field often reside with being the only or one of few women in the trade,” said Norton, who works for a distribution company in Canada. “Building a network of other women in the field helps women to overcome those challenges by knowing you’re not alone, having a supportive network and resources to connect to.”

Over time, however, Norton has noticed more opportunities for women in the line trade in her area. “There was a time when I was new in the trade and looking for an opportunity as a woman meant that you had to work harder to have someone to take a chance on you,” Norton said. “Increasingly today, women are seen and accepted as capable in the trade, and those without women are often asking what they can do to better attract diversified talent.”

Case in point: She recently received a photo from a woman who has been connected with Women of PLT since she was in her first year in the Powerline Technician program.

“The picture was of her and another woman powerline technician working aloft from a bucket truck,” she said. “To be at a time and place where we are seeing women powerline technicians working together has been wonderful, because for much of the time past there were simply too few women in the field for this to happen.”

Here are the stories of six women in the line trade. They are all at different points in their careers and got into trade for different reasons, but they all share a love for line work and can’t imagine doing anything else.

Corry Ruch of Hydro One

In 2019, Corry Ruch became the first woman to win an award at the International Lineman’s Rodeo. As part of a senior team from Hydro One, which also included Rudy Kerec and Richard Smedley, she said it was an unforgettable moment to win second place in the senior team division.

“Walking across the stage as the first female was one of the best experiences of my life,” said Ruch, a power line maintainer. “It made me realize that females can do it, and also, that it’s a team effort. At the Rodeo, everyone was so excited and happy and willing to help each other out.”

As the daughter of a nurse and a police officer, Ruch had her sights set on sports medicine or forestry following high school graduation. When she walked by a job board, however, a flier caught her attention: “Looking for Females in Non-Traditional Trades.”

After closer inspection, she learned that Ontario Hydro (now Hydro One) was searching for job candidates for its power line technician program. “I didn’t know what I was getting into, but I wanted to work outside,” she recalled.

Out of hundreds of applicants, only 35 got interviews for physical testing and an interview and five were hired in 1988. As part of the interview process, she had to climb a tower, drive in a ground rod and use a grip and chain hoist to prove her tool dexterity. Meanwhile, job mentors walked by the candidates to observe their skills and give a thumbs up or thumbs down. Five women were hired, and one quit before the end of the six-month period, leaving Ruch and three other linemen — Linda Monroe, Laurie Walsh and Janette Smit, who have since retired from the industry. Then in 1990, the utility hired three more female linemen.

When she first started out in the trade, a lot of the older linemen served as mentors, and she and the other women learned from them. During her apprenticeship, she had the opportunity to move around the service territory and learn about the different types of work.

One of the challenges she faced, however, was that she had to prove herself every single day on the job.

“If you are one of the only females in the trade, when people see you, they may think you are not doing the job,” she said. “You have to gain the respect of your fellow coworkers and enjoy what you do.”

For the last 34 years, Ruch has loved all aspects of line work—from getting the power back on after a storm to building lines and making the customers happy.

“I enjoy being outside and the physical work,” said Ruch, who teaches fitness classes in her spare time. “It’s important to remember that line work is not just a job—it’s a career, and you have to love it. If you are hired into an area, you are responsible for taking care of that area and keeping the power on for the people.”

In like work, you also have to get along with other people and troubleshoot problems. “Not everything is black and white,” she said. “On a trouble call, you just have to figure it out. While it’s great money, you have to want to do it. It’s not a 9 to 5 job, and you have to be physically fit because the job is demanding at times, and you are outside all the time, even in a snowstorm.”

Working storms, however, is her favorite part of doing line work, she said, looking back to an ice storm back in 1998. “When you go out and see the devastation that Mother Nature can do and know that you can fix it and get power back on efficiently, it’s very rewarding,” she said “All we need is a thank you to make us feel wanted and good inside.”

Ontario recently had a career fair, which features other females in the trades from brick layers to electricians and construction workers. The women talk to the high school girls, who often haven’t heard of the trades. “It opens their eyes that they don’t have to go to the university or college,” she said. “If they get into the trades, they can earn good money and have great careers.”

Other utilities throughout Canada have hired women as linemen, but most are just starting off in their careers.

“It takes about 10 years to see if they will last or not,” she said. “It’s a very challenging career. If you want to start a family, it’s hard to be away from them. It’s also physically demanding, which I quite enjoy, but for some ladies, it takes a while.”

Ruch has been married for the past 32 years to a retired lineman who knows the ins and outs of the line trade. They met at the Hydro School in Orangeville, Ontario, and the rest is history. While they never worked together during their careers, they both shared an appreciation and passion for line work.

“I stayed in the country, and he stayed in the city during our careers in line work,” she said.

They have one son, Brayden, who is now 24 years old and works as an electrical engineer for Hydro One. “I am very proud of him,” she said. “He creates the drawings for us to follow when we are going out on a line.”

When they both had to go out on a storm when he was young, their friends stepped in to help. “He knew that if there was a storm, we were going to have to go work it,” she said.

Now that she has more than three decades invested in the trade, she said she wants to stay in the field. Once she retires, she plans to help the apprentices, teach fitness classes and travel with her husband and enjoy her retirement.

“My career is coming to an end, and I plan to retire in the next year or so,” she said. “I’m not ready to go yet. Even after almost 35 years, I still love it.”

• • •

Lorrie Reece of Southern California Edison

As the daughter and granddaughter of journeymen linemen, Lorrie Reece had the opportunity to learn about the line trade from an early age.

“I was fascinated,” said Reece. “I was always amazed by what my father did. My first speech in seventh grade was about a transmission line that he was a superintendent on.”

At the age of 30, she started out as a groundman, mostly due to the fact that her dad steered her away from the trade. Once she got through the program, however, and her dad was very proud of her success.

She said she enjoyed being part of the apprenticeship program, and she never allowed herself to be looked at differently because of her gender.

“When a female enters a ‘man’s world,’ you have to be of a certain character to accept that if you are offended by behavior that is common to the position you don’t belong there,” said Reece, who has met several female journeymen linemen during her career. “I continue to have great relationships with former classmates. The challenges I faced were no different than anyone else faced. Line work is line work. You either have what it takes, or you don’t. That knowledge got me through some pretty difficult times.”

Reece’s whole family is in the trade, from her husband to her stepson. Her cousin also works as a lineman, and her uncle is a telephone lineman.

”I have a very forever marriage with a journeyman lineman who has been very successful and a stepson who is a troubleman for the same company that I now work for,” she said. “All has gone well for me, and I am very willing to share what I can with others — male and female — to achieve the same success.”

Reece spent 11 years “in the tools,” but orthopedic surgeries due to line work and her love for horseback riding led her to move from the field to the office.

“When it came to a point with my really bad knees and other orthopedic issues, I realized in order to be productive in the trade I had to change my avenue,” she said. “I went into safety on the contract side during recovery from a wrist surgery. I intended to return to my tools and realized I could make a difference without being on the pole or in the bucket.”

Reece is now a technical specialist with Southern California Edison Construction Methods. As part of her job, she answers work method questions around standards, installation and what types of materials to use for projects throughout the utility’s 50,000-mile territory.

Since she first started in the line trade, she said the industry is very different, the equipment is more advanced and the safety is improved.

“The PPE is far better than when I started,” she said. “The fall protection is incredible. You cannot hit the ground if you use it right.”

In the future, she would like to see more journeymen linemen concerned about the duty of a lineman rather than the great pay. She said for women to succeed in the industry, they must think of themselves not as a woman, but as a future lineman.

“Take the woman equation away because separating yourself doesn’t do anyone any good,” she said. “Opportunities for women are as open as they are for men. Pursue your options yourself not as a woman but as a human being who has a desire to do the work. It’s as simple as that.”

She said to get more women in the line trade, communication is key. “The only reason I was driven to it was my family, and not everyone has that advantage,” she said. “My favorite part of being a line worker is that I can be proud of what I and several family members have chosen because not everyone can do this thing that absolutely everyone needs but I can.”

• • •

Renee Nickles of Portland General Electric

As a single mom of a baby and toddler in the 1990s, Renee Nickles said she struggled to get by. She even worked as a bellhop carrying luggage. Then, line work came across her radar, and her world changed.

For most linemen, a family member or friend often serves as a source of inspiration to go into the trade, and Nickles was no exception. Her grandfather worked as a lineman for four years before he emigrated from Sweden to the United States.

“He took a boat, ended up at Ellis Island and started a new life in the United States as a carpenter at a local union in St. Paul, Minnesota,” she said. “I never forgot his stories, however, about how line work could provide a good income and strong future employment options. If I hadn’t had so much struggle at the beginning of my life, I may not have embraced it the same way.”

She decided to follow in her grandpa’s footsteps and enrolled in a three-month pre-apprentice program through the Spokane Community College. A trades program exposed her to all the available job opportunities. At the same time, she brushed up on her math knowledge, focused on test preparation and worked on her physical fitness.

“At that point, I remembered what my grandpa had done and all the challenges he had faced,” she said. “I knew it was a tough trade to go into, but I fell in love with it.” In the beginning, she was challenged with working around tools and getting in shape to handle the workload. Just like her male counterparts, she had to practice until she mastered certain skills. Oftentimes, she practiced on her time off or lunch time.

“I had to work on my stamina and the endurance of the job,” she said. “Line work takes a lot of upper body strength, and I built muscles I didn’t even know existed.”

At the same time, she had to be mentally resilient during the training program. “Quitting was never an option,” she said. “I never wanted to take a knee during the training. I had to put food on the table for my children and my family. I learned to dig in my heels until I got it right.”

In the late 1990s, she earned her journeyman card, and her adventure as a lineman began.

“It was a great feeling to have,” she said, recalling how she was driven to be self-sufficient. “I knew I could take the card and afford peanut butter sandwiches for my kids and the jelly to go on them. I could buy the Kool-Aid and the sugar to go in it.”

From the day she earned her card, she wanted to be called a “journeyman lineman.”

“I didn’t want to create any gaps by saying, ‘journey-woman,’” she said. “Because of the history and all the tough work, don’t devalue me. I earned it and worked hard for it.”

She kicked off her career by working with contractors, and when she had to work storms, her friends from her church helped watch her two sons, John and Josh.

“There’s a lot of guilt when you’re a single mom,” she said. “I couldn’t provide them with a father or another father figure, and I had to work long hours. It was hard to come home, and my kids said, ‘Mom, I missed you. Can you stay home?’ When they got older, they understood why I had to work. I was really blessed with the family and friends who helped me in my journey.”

After becoming a journeyman cableman, she left the area and moved south to work for Southern Company. Two years ago, she decided to move to Portland to become a field operations supervisor for PGE.

“When my kids were grown and out of the house, I wanted to go back to the Northwest,” said Nickles, whose is now remarried and whose sons are now 31 and 33 years old. “I also wanted to go back into the field of my first love, which was line work.”

As the manager of the line center in Portland, her day starts at the crack of dawn. She wakes up at 3 a.m. and arrives between 4:30 and 5 a.m.

“I like to get here before my team to gather my thoughts and look to see if there are any callouts or emergencies,”

she said.

After reviewing the work scheduled for the day, she meets with the lead working foreman to manage manpower. “If you want to come in the field and be in operations, you have to pivot continuously,” she said. “Maintaining safety is a number one priority. There are always emergencies going on.”

When Nickles first started out in the line trade, she had to wear men’s clothes and custom order specially made work boots. Fast forward to today, and she is having a hard time finding women’s flame-retardant shirts that she can wear not only in the field, but also in the office and when meeting with customers.

As the only female in the field many years, she not only had to deal with the lack of PPE designed for women, but also sensed men in the industry didn’t want women working with them.

“The men didn’t want to pick up the slack,” she said. “They anticipated failure because of the physical part of the job. If given the chance, women who are seeking to be linemen are capable and can do the work.”

Even today as a supervisor, she goes into places where they have never had a female boss before. “I came into their world, and I am very sensitive to that,” she said. “You want to be a good leader and be able to have the hard conversations and listen to their concerns. I have seen women come into the field who are very demanding, but I think it’s very important to connect with those you work with.”

When working with men, she said it’s important for women in the line trade to show both grace and mercy.

“You have to teach them how to work with a woman,” she said. “They have been working for years for each other, and you have to give them a little time to learn how to work with us. If they say something in front of you that you don’t appreciate, let them know it bothers you.”

Once her male coworkers noticed she had a passion for the job and wasn’t giving up, they supported her in her career. “They gave me tips and went out of their way to help me,” she recalled. “Sometimes when women go into the trade, they shy back from doing that. It’s OK to fail, but you have to get up and do it differently, or better, the next time.”

She urges young women interested in the line trade to seek out a local power company or union, search for apprenticeship programs and explore different trade schools. To gain experience, women can apply for entry-level jobs to learn skills like barricading and flagging to break into the world of line work and meet line crews. Local groups can also provide support. For example, the local Oregon Tradeswomen group, however, provides outreach to trade colleges, tech schools and utilities.

“From when I started in the trade to now, there has been a huge difference,” she said. “When I grew up, I took home economics, and it would be so nice if we could expose girls to more of the industrial arts like welding and plumbing. We still have some culture reflections of women doing the physical tasks, but those options are changing for the better.”

Now that she has moved into management and returned to working in the field, she will always remember her beginning in the line trade. To help others, she shares her story with women who are homeless or have been incarcerated in the Portland area.

“I will never separate myself from the single mom in me that struggled to make ends meet and make a career,” she said. “I help with the programs that get people back on their feet. I tell them that it is never too late to be self-sufficient. Having that passion for the community is my defining moment because it can give others success.”

• • •

Rae-Lynn Hawco of Valard Construction

Rae-Lynn Hawco happened upon the line trade. She was enrolled in another college program when male friends in the powerline course encouraged her to apply.

“There was an opening, and I made the switch and have never looked back,” Hawco said. “That decision was the best thing to happen to me.” Her grandfather, who worked as a red sealed heavy equipment technician, encouraged her to consider a career in the skilled trades.

“He always encouraged hard work in order to reap rewards and was a huge influence in my upbringing,” she said. “I also received tremendous support from my family and instructor, who gave me the confidence to excel in the line career.

Hawco, who won Canada’s most powerful women top 100 in skilled trade award for 2020, said in line work, it’s paramount to maintain a positive “can-do” mindset. “I learned it is important to give and take, have fun and ensure those around you have confidence in your abilities,” she said.

Her career-defining moment was obtaining her red seal journeyman certificate. Looking back, however, she describes her apprenticeship as challenging and intimidating because line work is a male-dominated trade. For example, as a woman, it was challenging for her to have the strength for heavy lifting, which required her to find a technique that worked for her. Also, when she started in line school, she had to learn things the old school way. For example, when drilling holes, she had to use a brace and a bit. Now that she is in the trade, she has access to top-of-the-line power tools to complete job tasks.

Another challenge was finding the proper footwear and work clothing. She finds it’s still hard to find climbing boots in women’s sizes or personal protective equipment for women. To meet this challenge head-on, she is teaming up with MWG Apparel, an FR clothing company in Canada, on an advisory committee on women’s PPE.

“I’m hoping to improve and expand on PPE for women in the line trade,” she said.

Over the years, she said she has witnessed marked improvements in the health and safety aspect of line work. “Line work can come with dangers, but I am reassured the appropriate checks and balances are in place,” she said.

Currently, she works as a journeyman lineman and quality analysis/quality control inspector for Valard Construction. In this role, she is working on a 230 kV H-frame transmission wood pole line and has a 21-days-on and seven-days off shift. She is responsible for inspecting framing and setting, fixing deficiencies and then performing a walk through with the client for the sign off. In addition, she runs a crew for fixing deficiencies and filling in on framing and setting crews when needed.

For the last eight years, her favorite part of the line trade is traveling for work, seeing new places, meeting new coworkers and soaking in the views working in the air.

“I’m trying new things and challenging myself in parts of the line trade I’ve never done and need experience in,” she said.

Compared to when she was an apprentice, she said there is now more female interest now in the line trade. Women in Canada must complete a powerline program and then work for contractors or utilities.

“I think it takes an interest in the trade and also seeing other women in the trade enjoying it, excelling in it and knowing that they have support,” she said.

Social media has been an excellent medium for female line workers to connect with each other, she said. “I participate in a Facebook group, which enables sharing of knowledge and information,” she said. “In addition, I am active in Women of PLT, offering funding and mentoring for women in or entering the trade.”

She said she prefers to be called a “linewoman” rather than a “lineman” or “power line technician.”

“I feel like that word feels strong,” she said.

• • •

Paige Spietz of Evergy

Paige Spietz, a college basketball player who earned her degree in environmental science from the University of San Francisco, never envisioned a future career in line work. She started her career as an arborist contracted by Kansas City Power & Light (now Evergy), where she now works as an apprentice lineman.

“When I was an arborist, I walked many miles a day, looking at trees around power lines,” she said. “I was always curious about what the equipment was doing, and where it was feeding power to,” she said. “It was a different transition working with trees and then moving to climbing poles, but it helped me to get into the swing of things.”

Once a month, as an arborist for ECI, she visited the operation centers, and the linemen convinced her that line work could be a great fit for her. “I was familiar with the buildings and the people, and I knew some lineworkers who worked at Kansas City Power & Light,” she said. “It was a good way for me to find myself a career.”

When she told her parents that she wanted to go to line school, her mom was worried about the dangers of line work, while her dad backed her 110 percent, she recalled.

“I have a good support system,” she said. “I think my friends are also proud of me.”

She enrolled at the line school program at Kansas City Metropolitan Community College, where Susan Blaser, the leader of the program, is the first woman lineman in Missouri.

“I listened to her talk, and her experience gave me the confidence that I could do it,” she said. “There’s not a lot of women in the field, but I am now talking to other women in the trade and there is a lot of support there. This is how I got into line work.”

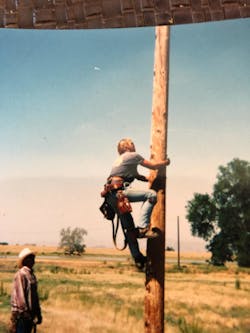

At MCC, Blaser taught her how to climb low and slow on the pole using a climbing belt and BuckSqueeze from Buckingham Manufacturing. After a few hours, Blaser instructed her and the other students to climb to the top.

“When I look back now, I can’t imagine how I looked climbing that pole,” she laughed. “It’s a crazy experience because you are 40 ft in the air after basic training on the equipment,” she said. “That’s when you figure out if it is or isn’t for you. I’ll never forget my first time in the air on my hooks.”

She said she fits perfectly in the world of line work. “I loved the physicality of working as an arborist, but I was searching for something more,” she said. “It hit me when I was on the pole for the first time how much I loved being in the hooks up in the air. To be outside every day and work on power lines and poles intrigued me.”

Ten years ago, she was afraid of heights, but since then, she has climbed hundreds of poles when doing line work and enjoys every minute of it.

“One of my favorite things is like basketball, you can be as good as you want to be in line work,” she said. “This trade in my eyes is the same. You may start somewhere, but there is no ceiling. There is so much to learn and love about this trade.”

She is now one of two women in the line apprenticeship, and a few female journeymen linemen work at Evergy. As a second-year apprentice, she said she faces the same challenges as her male counterparts.

"You are constantly being evaluated with what you are learning, how you are retaining the information and how you are moving forward with the physical work,” she said.

As an apprentice, she said she enjoys the work because she gets to have her hands on every task.

“We work on every job we do by pulling a lot of the material, loading the poles and transformers and driving the big trucks,” she said. “It’s really cool that we have the chance to learn so much and get to be in the bucket all day every day.”

One of her favorite parts of line work, however, is working storms. The Midwest is challenged with intense heat to snow and ice storms, and she loves being out with a crew on a storm.

“It goes back to playing basketball my whole life,” she said. “I have the gamer mentality. I love being in the zone and focused on work. When the lights are out because of the weather, being with a crew on a storm is so fun to me. Being in the trench with the guys takes me back to the mental state of playing basketball.”

In line work, just like in competitive sports, it’s essential to be physically active and in shape to do the job, she said. Battery-powered tools, however, have opened the doors for more women to enter the trade.

“Over a 30- to 40-year career, line work can take a physical toll, but these tools make it so much easier on the body,” she said. “If more women knew about the trade and the fact that you don’t have to be a bodybuilder to succeed in line work, I think we would have more women.”

In addition, apprentices must enjoy the work.

“If it is something that is interesting to you, you will work hard and put the time in to get better every day,” she said. “It’s the same thing for a male in the trade. I think if more women knew about the trade, we would have more success as linemen.”

At this point in time, she said so many opportunities are available in the line trade. Linemen can work in any state or anywhere in the world.

“I never thought I would be a lineman, and I think women don’t know they can be successful in this trade,” she said. “The opportunities are endless in my mind. You can go to a line school, get a degree or a certificate and start a career in line work that can be amazing. I want to spread the word about women being able to do this job.”

When she was in high school, she said the trades often weren’t talked about, but she is changing this for future graduates.

“I have done a few video conferences and recorded videos for students in tech schools, which was super beneficial,” she said. “I want to get the word out to both male and female students about why they should pursue a career in line work.”

When she tops out as a journeyman, she said she will prefer the title of “lineman.”

“This job has been around for a long time, and it doesn’t make sense to change the word just because we are finally getting more women in the trade,” she said. “It’s up to whoever is doing the job, but what I am totally OK with the word, ‘lineman.’ Being a woman in the line trade is not any different than being a man. The difference is that there’s not that many of us. I’m just trying to be the best lineman I can be.”

• • •

Lana Norton of Women of Powerline Technicians

As a young mom without a post-secondary education, Lana Norton discovered that the shortest path to securing financial stability was pursuing a career in the trades.

“Through an early exposure to electricity, understanding how electricity moved came naturally to me,” she said. “When I realized I would rather be at heights and outdoors than wiring indoors, powerline became the only option.”

In 2010, when she was in college, the Powerline Technician program was brand new. Norton became the second woman to graduate. Today, she is the chair of the Program Advisory Committee for Electrical Engineering and Powerline Technician programs at Algonquin College.

“I accomplished what I set out to do in the beginning, which is providing financial stability for my daughter,” said Norton, who is now pursuing a bachelor’s degree in business administration.

Upon graduating from the Powerline Technician program, a local distribution company hired her as an apprentice powerline technician, and she has been with the company ever since. Over the last decade, she has had various trade and technical roles in distribution operations. As a field operator, she responded to electrical emergency situations to safeguard people and assets and operated high- and low-voltage distribution systems. She then moved on to the role of a field technician, and as a member of distribution engineering and asset management, she ensured construction projects adhered to business performance and scheduling timelines and were ready for execution by field crews.

Currently, she serves as the supervisor of metering field services and oversees a team of meter technicians. In this role, she is responsible for the day-to-day execution of all metering equipment operation, metering equipment installations, maintenance and renewal of the assets.

Every morning she prepares her team for the jobs of the day and reviews jobs, timelines and resources available to complete the work. She said it’s her favorite part of her day.

“I get to hear about challenges they see in the field and then I do my best to help them overcome the challenges through collaboratively working with stakeholder groups, refining processes, or preparing for upcoming projects to keep the work going and the team happy and appreciated,” she said. “During the day, you’ll also find me attending meetings related to upcoming metering work and out on the job site checking in with my team.”

Norton also serves as the executive director of the Women of Powerline Technicians, which she founded in 2016.

“After graduation as my peers and I went onto work across the province, they would reach out to me as they met other women working in the trade,” she said. “Over time, the network grew.”

Norton describes the organization as “the voice from the field committed to increasing women in trade and technical roles in Canada’s electricity sector and beyond.” The mission of the national not-for-profit is to have women as equal participants in trade and technical roles in the electricity sector.

“People and the pursuit of advancing the future of the electricity grid is my passion,” she said. “There is camaraderie with women PLTs, and the best way to find it is connecting with Women of Powerline Technicians. We are an organization built on supporting women in all their diversity in the electricity sector and line trade.”

The group advises leaders through a gender equity lens on how to advance their diversity and inclusion goals. Secondly, the group offers programming open to both men and women.

“We have a focus of supporting women in early, mid, and late careers in the trade and technical roles,” Norton said. For example, the group’s programming includes mentoring, 24/7 Peer Group, career postings, networking events, Bursary, and The Illuminate Blog, which features interviews of women lighting the electricity sector.

As she enjoys today and all she has been able to achieve, in the future, she would like to contribute in a larger way to multilateral grid sustainability and energy policy.

“We exist in a place where power has become a necessity and time without it is measured in minutes,” she said. “This speaks to the astounding reliability of our electrical systems and to the people who we are accountable to, our customers. As we look to the future, I am excited by the possibilities distributed energy resources bring to our grid capabilities and the ways electricity will evolve to meet the expectations of our customers.”