In college, I suffered the indignity of an OPEC-inspired oil crisis. It was very real and very ugly, with high gas prices and low availability. Lines formed that traversed blocks. Arguments and fights awaited anyone trying to break in line.

With predictions that known oil reserves would decline and with emerging economies consuming more oil, I was pretty sure I would be one of the first consumers to buy an electric vehicle when they came onto the market. But today, almost 40 years later, I have yet to purchase my first electric vehicle.

In fact, it took another 20 years before General Motors brought the EV1 on the market, and it arrived to a lukewarm reception. The EV1 was available from 1996 to 1999, but by then, I had a wife and three kids, and my priorities had shifted. I was more interested in seating capacity than fuel availability. And with more oil reserves discovered, OPEC no longer had a stranglehold on the fuel supply chain.

While digging around, I found that the EV1 wasn’t the first production electric vehicle made in the United States. Back in 1890, William Morrison from Des Moines, Iowa, offered a six-passenger electric vehicle. By 1900, more manufacturers had entered the business; so many, in fact, that electric cars made up a third of all vehicles on the road.

But because EV cars had shorter driving distances than internal combustion engines and because of their inherent long charging times, EVs were soon losing market share to gasoline-fired automobiles. That is until 97 years later, when Toyota came out with the world’s first mass-produced gasoline-electric hybrid in 1997. Elon Musk repeated history in 2010 when he announced that his all-electric Tesla Model S would be manufactured in Fremont, California. Nissan shortly thereafter rolled out its all-electric Leaf. Today, many startups and most mainstream car makers offer all types of electric vehicles. But what really caught my attention is this recent summary of major automakers committing to the EV market.

Here is what Sarwant Singh wrote in an April 3, 2018, Forbes article: “Porsche aims at making 50% of its cars electric by 2023. Jaguar Land Rover has announced it will shift entirely towards electric and hybrid vehicles by 2020. General Motors, Toyota and Volvo have all declared a target of 1 million in EV sales by 2025. By 2030, Aston Martin expects that EVs will account for 25% of its sales, with the rest of its lineup comprising hybrids. By 2025, BMW has stated it will offer 25 electrified vehicles, of which 12 will be fully electric. The Renault, Nissan and Mitsubishi alliance intends to offer 12 new EVs by 2022.”

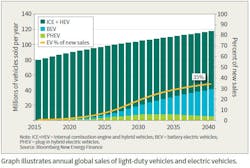

As battery costs continue to drop and as manufacturers give customer more choices, Forbes predicts we will have 25 million EVs on the road by 2025. That’s not that far away.

Undeniably, electric transportation is on the upswing. For my birthday, my daughter, my wife and I rode our new hop-on, hop-off electric trolley that runs right down Main Street here in Kansas City. My wife also recently drove a friend’s Prius. Now when her 10-year-old Toyota Highlander reaches its end of life, her first choice will be a Prius.

What’s a Utility to Do?

Charging an electric car from the grid could be equivalent to adding two or three houses to the grid. This would require investments in the delivery system as EVs become more widespread. Of course, the impact of charging an EV is dependent on where it is located on the grid and the time of day it is charged. Bloomberg New Energy Finance expects EVs to reach price parity with their gasoline counterparts by 2022 or sooner. At that point, expect sales to rise quickly. We have a little time to get our grid ready to accommodate EVs but we can’t afford to squander it.

Expect rates that encourage off-peak charging and on-peak discharging. And with more of us working from home, and with systems getting smarter and smarter, deciding each day to sell all or a portion of the electricity stored in our EVs the night before will get easier and more intuitive.

Utilities are predicting flat to declining electricity sales in many parts of the country as consumers reduce consumption and as they add distributed energy resources on their side of the meter. The load and resulting revenue that will come from EV charging could be the white knight for our utility needs.

As for my family, put us on the “To EV” side. I mentioned earlier that my wife wants a Prius, and with the right financial incentives, we would go all in and select a vehicle and a charging system that would have us selling power back into the grid.