Several weeks ago, I asked what turned out to be a bit of a “hot potato” question for our IdeaXchange Xperts regarding next-generation regulatory models, and my question led to a couple deeply considered replies.

My question was prompted by Michael Heyeck’s November 2015 NexGen Utility Leaders IdeaXchange commentary, where he looked back 60 years “to extrapolate the foundational elements needed for the next-generation utility.”

I suggested in my introduction (now the conclusion below) that we look even further back, for an even broader perspective, when it comes to NextGen Regulatory Models.

I reviewed the contributions of a key founding innovator in our industry, Samuel Insull, and the subsequent 100 years of changes that led to the Enron crisis and to the upcoming changes our industry is now facing.

Here was my resulting question:

How would you revamp our regulatory models and related business models so that our industry can optimize potential benefits of a smarter grid while ensuring ongoing key goals of serving the public with economic rates, operational excellence, high standards for safety and service reliability are still met?

Michael Heyeck

Thank you for the reference to my earlier IdeaXchange and the intriguing question.

The straight lines from source to load are blurred in a good way by a long trail of actions by federal and state authorities. From Thomas Edison’s original Pearl Street microgrid to vast interconnected system operations that can claim the title of the greatest machines humans have created, we seem to be evolving to micro mixed with the remaining economies of macro.

Today, forces of markets limited by rate fatigue have evolved the regulatory compact to "who knows?" Ingenuity in the United States has stemmed from the creative forces of chaos (figuratively, of course) and experimentation to yield a better outcome tested by market forces with success measured by the choice of the consumer.

The bottom line for me is to allow experimentation to occur and to recognize that regulators are only one part of that solution. Utilities must step up and not be defensive of tradition. Third parties should bring ideas to market. And regulators must stay a step ahead to enable.

But consumers pay the bills. Give them a commodity (electricity) and they will insist on the lowest prices. Give them a service they desire (comfort) and then the opportunity reveals itself.

I admire our regulators and tip my hat to them in these changing times. Their tenure tends to be brief yet their learning curve steep. Legislative reaction to help yields a long trail of rationalization (and work) that inevitably must by corrected. Regulatory staffs are the heroes behind the regulators.

If you are looking for the next-generation mustard seed in fertile soil, look at what the New York PSC is doing to understand. Their REV plan is truly next generation. Is it final? Absolutely not. The best recognize that learning from mistakes and other trials yields corrective actions that improve outcomes.

Another regulatory front to rationalize is the federal vs. state purviews. As we evolve from big wholesale markets via transmission grid operators to the integration of the virtual reality of micro markets enabled by distributed energy resources (DERs), we must rationalize the wholesale (federal) vs. retail (states) sandbox to unleash this future. Will DER aggregators be limited to the net-metering paradigm, or can they find value in the law of large (and diverse) numbers in wholesale markets with DERs? The legal challenge to FERC Order 745 is only a glimpse.

I leave you with this: Keep the consumer in mind, because they pay the bills.

Dr. Mani Vadari

The issue has three key elements from which I have three key takeaways:

- Regulatory models: The United States has possibly the most complex regulatory model. We have a complex set of interactions between federal, state and other jurisdictions, supported by a lack of energy policy at any level. As a result, every state functions differently and under a different set of rules.

I believe we have created a situation that is sorely in need of a change.

- Business models: Since PUHCA, the utility business model has been mostly unchanged with the exception of FERC orders 888 and 889, which resulted in the separation of wholesale generation from the rest of the utility.

I believe distributed energy is the disruptor that will challenge this model.

- Our industry: For the longest period of time, our industry has been focused on delivering reliable power to the customer. This mandate has almost been sacrosanct in that it has been the core mantra that has virtually driven every decision made by utilities.

I believe this mandate needs to stay. Electricity is too critical for just about everything, and civilization will come to a halt without it.

In the first set of questions we need to ask ourselves: "Is there a lesson to be learnt from the telecom industry?"

It is widely believed that while the breakup of Ma Bell in the mid-80s led to several major innovations including cellular technologies, the wide dispersion of the Internet, Voice-over IP and the Smartphone. Are there similar opportunities that await the next-generation electric utility, and if so, what would that look like?

Michael Heyeck mentioned distributed energy resources. DERs have the potential to allow the customer to take less power from the incumbent utility. Potential future technologies may allow the customer to completely disconnect from the utility.

Does that create the potential to create a stranded asset problem for the utility coming from customers purchasing less power from the utility for the same asset cost?

The example of an upstart telecom wireless provider such as Cingular buying out the AT&T and becoming the new giant that it is in all aspects of telecom, wireless, cable and so on leads to new lines of thought in our industry.

Is something like this possible in the electricity industry, and if so, who will be the first player? Will existing utilities have the incumbent advantage to move?

The New York REV effort of creating a Distribution System Platform (DSP) focused on standardizing the DER interactions in a state through the creation of a retail market, centralized planning and an independent grid operator is something that is being watched very carefully by almost every state in the country. In addition, several European countries are also experimenting with this model.

Will this or a similar model spread to other states in the U.S., and if so, what will be the role of the independent distribution operator? Will we finally get some level of standardization at the retail level, and if so, how will these entities interact with the wholesale markets?

The electric utility has survived for more than 100 years; Does it need to survive another 100?

Is there an alternative to today’s T&D approach to delivering power, and if so, (1) what would it look like and (2) when would it become a reality?

The second major question that still needs to be asked is: Do we still need an entity that has the job of ensuring ongoing key goals of serving the public with economic rates, operational excellence, high standards for safety and service reliability are still met?

I believe the answer to this is a YES; however, I am not sure whether the best way to achieve this needs to be the utility. In the near and mid-term, it does need to be the utility. The role of the grid as the infrastructure provider for the lowest cost electricity will not be in jeopardy.

However, in the long-term, this responsibility could be provided by any number of entities — some still fully connected to the grid, some using the grid as a backup option and some completely disconnected.

This movement away from a utility would be enabled by newer technologies such as microgrids, storage and other DER technologies and will accelerate as their costs come down.

However, the movement away from utilities is also not a foregone conclusion. As the current provider, they will have the best opportunity to continue their present strong position, but they will also need to transform themselves into the most optimal and flexible provider of services focused on the customer instead of the infrastructure build-out.

So what?

As can be seen in this blog, there are more questions than answers. Given the pace of change, one cannot predict where this future will lead us — but one thing is certain — today’s utility will need to change, and today’s regulatory regime will need to change.

If these changes do not happen, we will have an extended period of chaos before the legislative arm may need to jump in and enforce something that may make the situation worse.

Peter A. Manos

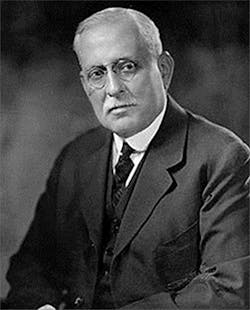

Let’s trace our foundation back to a key player in our industry’s early history: Samuel Insull.

In 1892, Insull became president of Chicago Edison and within two years built what was then the largest central generating facility in the world — Chicago Edison’s 16 MW Harrison Street Station.

Samuel Insull grew Chicago Edison by expanding capacity and cutting rates for many years.

In today’s parlance, we might say that Insull bought and connected a bunch of previously disconnected microgrids.

Much of Insull’s success stemmed from his insights about diversity of load. The diversity of load concept, which is familiar to any utility engineer, has been a key economic driver for the growth of the electric utility industry.

Diversity of load is important because the times of peak electric usage vary between one customer location or load and another. Let’s say you were dealing with a situation similar to what Insull first saw when he came to Chicago, where many separate loads were each served by their own dedicated, isolated microgrids. Each of those generating units would have to be sized to meet the peak demand of its location, a demand value only reached for a few minutes every day. Insull realized if he connected those isolated loads and serve them from centralized generating facilities, the overall electric capacity needed to meet the collective peak demand would a lot smaller.

Insull leveraged the benefits of diversity of load by buying up and connecting as many islanded loads served by stand-alone generating facilities as he could, and also by lobbying for business models that facilitated investments in the grid which created great economies of scale.

His vision was to give monopoly power for utilities in their geographic territories, while protecting investors and the public by ensuring state regulation checked monopoly power and ensured fair electric rates.

Things went well until the crash of ’29 and the early 30s.

A backlash against monopoly power occurred. Fear that Insull’s model had gone too far led to enactment of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA).

Prior to PUHCA, in the early 1920s, electric utilities were the largest sellers of washing machines and refrigerators. Utilities in recent years have been getting back into consumer engagement, restarting “other side of the meter” marketing that had been shut down by regulations for many decades.

Our industry enjoyed tremendous growth between the end of WWII and the mid-1970s. This reduced the risks associated with capital investments utilities needed to make, because the GDP and population growth engine ensured most over-spending associated with near-term over-building of generating capacity or T&D infrastructure would soon be absorbed in electric rates.

Things changed in the late 1970s and with The Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) and the events that followed, the regulatory pendulum began its swing the other way….until the changes that occurred in response to the Enron Crisis.

A report in the Energy Law Journal: “From Insull to Enron: Corporate (Re)Regulation After the Rise and Fall of Two Energy Icons”, places the Enron Crisis in a big context. The authors, Hon. Richard D. Cudahy and William D. Henderson, make interesting analogies between Insull’s promotion of investor-owned utilities versus municipal utilities, with a “vast propaganda campaign to highlight the benefits of privately owned utilities and the evils of public power,” and how, 70 years later, Enron “embarked upon a lavish public relations effort designed to educate consumers (and voters) on the virtues of electricity deregulation.”

What Cudahy and Henderson say at the end of their report is striking: “…There is a serious risk that policy prescriptions flowing from the Enron debacle will ultimately be thought of as equally obsolete by the time another “Enron” arrives on the scene…. Perhaps the most plausible recipe for an electric power system is to mix in equal parts economic theory and brash pursuit of power of the human sort. This is the volatile mixture that came to life but eventually led to death at Insull and Enron.”

Let’s consider energy efficiency and other initiatives that tend to reduce utility revenues, as well as the big investments required in market research, marketing and technology, to fully deploy wide-ranging smarter grid programs including those that require TOU-based rates and real-time data.

Technology life cycles appear to be speeding up. Are our regulatory mechanisms keeping up with the pace of change?

We have chasms to cross but cannot do so with baby steps without falling into those chasms!

These ideas led to my original question: How would you revamp our regulatory models and related business models so that our industry can optimize potential benefits of a smarter grid while ensuring ongoing key goals of serving the public with economic rates, operational excellence, high standards for safety and service reliability are still met?

Afterthoughts

It is interesting that Michael Heyeck’s reply and Dr. Mani Vadari’s reply both refer to the role to be played by chaos in the changes that lie ahead.

I see us as having come full circle, to last November’s inspiration for this IdeaXchange, since we will need next-generation utility leaders to cross those chasms, stepping into new markets like the New York Rev and transforming them.

They are the leaders Michael referred to as “change agents who know no boundaries.”

For what is chaos, but a place with unknown boundaries?

Please feel free to join the discussion in the comment section below.