Once viewed as an isolated market with limited lessons to offer global markets, Australia and Alaska have emerged as leading voices in articulating how best to accelerate the transition to a net zero energy economy. Part 1 in this series focused on the two countries common reliance upon microgrids to serve isolated communities, and market reform, which couldn’t be more different. In Part 2 we look at the role hydrogen will play in clean energy transition.

Translating the Hype on Hydrogen into Commercial Reality

Both Alaska and Australia are committed to hydrogen as major path to decarbonization. Alaska’s forays to date have largely been conceptual and are focused on piggy-backing on the extensive oil and natural gas development that has made Alaska famous worldwide in the past. Australia also shares a history of extractive industries with Alaska but is moving much more rapidly with renewable energy-based hydrogen projects with four major large scale projects already underway. Here is a brief description of these four mega-projects:

- Australian Renewable Energy Hub. This project dates back to 2014. It has undergone significant revisions along the way. With BP in the lead, the project also includes CWP Global and Intercontinental Energy. The ambitious project would be supported by 26 GW of combined wind and solar capacity, an amount of clean energy equal to roughly a third of Australia’s total electricity generation in 2020. That amount of new renewable capacity would create 1.6 million tons of hydrogen (or 9 million tons of green ammonia.) The project could reduce Australia’s carbon footprint by 17 million tons annually.

- Western Green Energy Hub. This project also includes both CWP Global and Intercontinental Energy, but this time the third partner is Mirning Traditional Owners, a group representing local indigenous peoples. The project is projected to generate 50 GW of new solar and wind capacity, enough renewable energy to create 3.5 million tons of green hydrogen.

- HyEnergy Project. This project involves another global oil company – Total of France’s independent power producer arm Total Eren – and partners Province Resources Limited and Provaris Energy. It is already under development and its size was increased from 1 to 8 GW of wind and solar capacity. It is estimated that it can produce 550,000 tons of green hydrogen annually upon completion, with phase 1 representing 4 GW of clean energy capacity. The project leverages existing pipelines and is viewed primarily as an export opportunity to decarbonize the Asia Pacific region.

- Green Energy Oman. The fourth large-scale green hydrogen project being co-developed by Intercontinental Energy is this project, which was started in 2018 and is based on development of 25 GW of renewable energy netting 1.8 million tons of green hydrogen. In January 2023, Shell, another global oil company giant, joined this project, the third major oil company to be involved with hydrogen development in Australia. EnerTech Holding Company, a state-owned Kuwait enterprise, is also a project partner.

Evan Gray stands in the hydrogen storage facility of the Sir Samuel Griffith Centre on the Griffith University’s Nathan campus in Brisbane, Australia. Photo by Amanda Byrd.

The Sir Samuel Griffith Centre was designed and built as a demonstration solar energy-to-hydrogen powered facility. To ensure it can provide power if the microgrid fails, the building is connected to Nathan, Queensland based, Energex’s local network. But its primary source is solar power that is used to generate hydrogen for additional power and energy storage.

The building’s 1,164 solar photovoltaic panels generate the base power for the building, and a battery bank made of 1,024 lithium-ion batteries stores power to be used at night and in inclement weather. When a battery bank is full, the solar array, which is oversized for the building’s needs, is used to generate hydrogen for long-term energy storage and additional power. The hydrogen is stored in stable, solid form as metal hydride. Heating the fuel cells releases energy and also releases hydrogen gas which can provide full power to the building for around three days.

As utility companies look to hydrogen energy and storage, they may look to Australia, which currently has around 120 hydrogen-related projects including 10 operating facilities, 12 under construction, 87 in development planning, and others in assessment studies.

The Sir Samuel Griffith Centre on the Griffith University’s Nathan campus in Brisbane, Australia uses solar power and hydrogen to power the entire building. Photo by Amanda Byrd.

Four major large-scale hydrogen projects involving three of the world’s largest oil companies are in the works. One could make the argument that Australia is currently the leading country in the world in committing to a hydrogen future.

How does Alaska stack up?

The short answer is there is no comparison. Nevertheless, Alaska does seem to represent the best hope in the U.S. for large scale hydrogen production hubs. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill of 2021 also provided the seed funding for 6 to 10 hydrogen hubs in the U.S., investing $8 billion over five years. The Alaska Gasline Development Corporation (AGDC), working with ACEP and other partners, has submitted a proposal to the federal Department of Energy to develop such a hub. Among the criteria for DOE funding is the ability to produce 50 to 100 tons of clean hydrogen daily. Grants can reach as high as $1 billion for a single project.

Why is Alaska poised to take the lead on hydrogen for the U.S.? Unlike Australia, Alaska could tap the enormous existing natural gas reserves in the state that have already been developed at a world-class scale. To meet the decarbonization metrics, Alaska also has significant potential for carbon sequestration. Along with enormous fossil fuel reserves, the state has potential for significant renewable energy development, including newer options such as tidal resources - Alaska has the best tidal resources in the U.S.

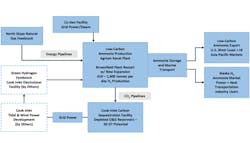

Perhaps the most important factor for hydrogen in Alaska is the availability of private sector funding to make these projects commercially viable. Alaska’s North Slope is North America’s largest untapped source of natural gas. Converting to hydrogen (along with liquified natural gas exports) is the best way to tap this resource without unduly accelerating global climate change. Cook Inlet in south central Alaska has the potential to sequester 50 gigatons of carbon in underground geologic formations. A project to do exactly that has been proposed but it is far from simple. The diagram below showcases the complexity and integration of several technologies and market players for this vision to become reality, including the integration of a decommissioned ammonia plant.

DOE Alaska Hydrogen Hub Proposal: Multiple Players; Multiple Products

The Alaska’s hydrogen hub proposed for Alaska involves multiple players and products generating multiple value streams across the energy ecosystem. For more information about hydrogen energy in Alaska, please join the Alaska Hydrogen Working Group.

Conclusion

Australia and Alaska have many similarities, especially when it comes to islanded power systems and microgrids. One interesting similarity is the need for space heating — or in Australia’s case, cooling. The solar-to-hydrogen facility’s largest load is in fact a chiller that provides 200,000 gallons of cool water for air conditioning.

Regarding the future of hydrogen technologies, Australia is far out in the lead. Yet Alaska with one of the most diverse renewable energy-based microgrid project portfolios in the world, could be positioned to lead the U.S. on hydrogen development. As the world transitions away from carbon fuels, industry stakeholders in Alaska have an opportunity to reinvent themselves. By transforming the state’s oil and gas industries towards hydrogen development, they can pave the way for large-scale infrastructure that creates significant economic benefits for Alaska while contributing to the clean energy transition in the most creative and cost-effective way possible.

Peter Asmus is Executive Director of the Alaska Microgrid Group an affiliate of the Alaska Center for Energy and Power (ACEP), part of the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Asmus is a leading global authority on microgrid markets and other emerging trends in sustainable and resilient energy systems. Author of four books, Asmus has been writing about and analyzing emerging trends in energy policy, technology and applications since 1986. Most recently, he was Research Director with Guidehouse Insights where he started up the world’s first global data set on microgrids and developed a forecast methodology to estimate future growth. He has served as a global thought leader on microgrids and other DER platforms such as virtual power plants. Among his past clients are ABB, ATCO, AutoGrid, Bank of Tokyo, EDF, Enbala (now Generac Grid Services), Engie, GE, Hitachi Energy, Horizon Power, Power Ledger, Schneider Electric, Siemens and many others.