After a recent visit to the Northwest Lineman College in Boise, Idaho, I was fortunate to receive a copy of Alan Drew’s wonderful new book on a seminal transmission project that was a tipping point in establishing the Northern California economy and by extension the Silicon Valley we know today. The full title for this large format book is, The American Lineman: Spanning the Strait. The subtitle is How the American Lineman Electrified the San Francisco Bay Area.

The book is available from the college at US$29.95, which I think is a bargain for something of this quality. However, the book’s title gives the impression that it only covers the 1901 completion of a 4,472-ft, 40-kV span (a world record at the time) across the Carquinez Strait in the northeast San Francisco bay, but there is much more than that.

The first chapter explains the history of power transmission, going all the way back to the Greek philosopher Thales to the infamous Nikola Tesla’s discovery of three-phase power. Up until this project in 1901, most of the innovation in long-distance transmission was happening in Europe, particularly in Germany, but surprisingly the first 4-kV transmission line built in the United States was from Willamette Falls to Portland, Oregon, in 1889 and was dc, not ac. We tend to forget that for engineers this was an exciting time of technological innovation in electricity generation, transmission and use — something we take for granted today.

Obviously, the other side of transmission is generation, and the Carquinez strait crossing was just one challenge in getting hydroelectric power from the Sierra Nevada mountains to San Francisco. The generating station for this 142-mile project was called the Colgate Power Plant on the Yuba river. It is fascinating to read that much of the expertise in hydropower came directly from Gold Rush miners who became experts in water diversion to uncover gold deposits. This project was a product of a power company called Bay Counties Power, which was a predecessor to the current Pacific Gas and Electric Company that with 15 million customers serves most of Northern California today.

The book reveals the colorful characters behind the project, such as Romulus. R. Colgate, who was a grandson of the Colgate Soap company founder and had the Yuba River hydro plant named after him.

Another important local engineer was Lester A. Pelton, the inventor of the Pelton wheel — which is a highly efficient water wheel design still in use today in water turbines all over the world.

Once the source was determined, the next challenge was to get the power to San Francisco. The book explains that since high-voltage technology was so new, the system hardware had to be literally developed and built using the trial and error method. For example, how were they going to insulate the conductors? Build switchgear? Design poles, towers and anchorages?

Then they had to put it all together and make it work reliably in all weather conditions, including lightning protection. The phrase “necessity is the mother of invention” comes to mind here because the engineers involved in the project invented the hardware they needed and laid the foundation for the modern T&D hardware we see linemen installing every day. The Baum oil switch, Locke Insulator, Stanley Electric switches (later General Electric) and the Roebling Company conductors were all developed for this project and went on to serve the industry nationwide.

Many people are familiar with the glass and porcelain insulator and there is a thriving community of collectors, who even have their own magazine called Crown Jewels of the Wire. One of the rarest insulators was the Fred M. Locke No. 316 insulator seen below. If you see one of these at a yard sale, you should consider buying it.

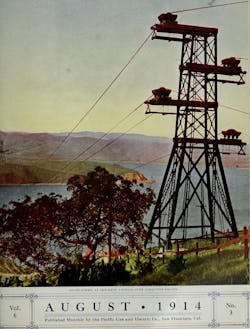

Alan goes on to describe the massive effort that went into building the anchorages and stringing the conductor using ships, steam engines and various pulley techniques, a true feat of engineering expertise for the time. Here is how it looked in 1914:

Reading Spanning the Strait was an experience slowly being lost in our digital world; it was the marvelous serendipity that can only happen when we immerse ourselves in a book; I would never have googled Lester A. Pelton and found out that Pelton wheels were cast in a downtown San Francisco foundry for over 50 years! Sometimes we need to give ourselves a digital break and explore a world we don’t know about; let go of our illusion of digital self-determination and just read.

If you are involved in the power industry I encourage you to get this book and learn about how we got to where we are today — you won’t be disappointed.