The Roaring Twenties

In just 16 months, a full century will stand between us and the start of the decade known as “The Roaring Twenties.”

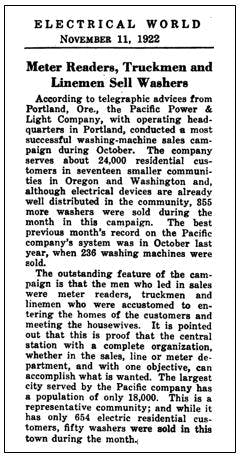

There is a youthful enthusiasm to be seen in electric utility industry trade press articles from the 1920s, whether the articles were written from the perspective of electric utility executives, engineers, or meter readers.

Beyond the enthusiasm of our industry’s “growth spurt” era, there are lessons to be learned today based on the high level of marketing savvy the electric utility industry had back then.

In terms of customer engagement, utilities in the 1920s were instrumental in getting end-use customers to see the economic value and personal benefits of using new electric appliances.

In addition, utilities also worked with manufacturers to ensure they could be relied on to meet schedules for delivery of new appliances and that these appliances were designed to be reliable and easy to service, thus setting a strong foundation for ever-increasing demand for electric service.

PUHCA as the Dark Ages?

Fundamentally, enactment of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA) coincided with the beginning of a long, drawn-out end of the era when electric utilities were leaders in “high tech” and had a culture (and influx of capital investments) envied by other industries.

While the main thrust of PUHCA was a bolstering of regulations in reaction to the stock market crash of 1929, with a cleanup of questionable business practices in relation to interstate utility corporate ownership and financial reporting, PUHCA also restricted how utilities could market to their customers. It put a stop to investor-owned utilities’ efforts to sell “behind the meter” products and services to customers.

Despite the period of sound financial growth and transparency for electric utilities after PUHCA, one may well say PUHCA ushered in the “Dark Ages” for electric utility customer engagement efforts because PUHCA closed direct utility involvement in a big portion of the type of customer engagement and marketing efforts that had been critical to healthy growth in the uptake of electrical appliances, electric heating, and electric lighting.

For the rest of the 20th century, after the enactment of PUHCA in1935, utilities were generally prohibited from engaging with customers for any behind-the-meter products and services.

A Pre-PUHCA Teachable Moment

Consider a true personal story. It is a story I heard in the early 1990s from a distribution engineer at Central Maine Power who was nearing retirement age:

“My mother told me about how she and Dad bought our first washing machine. The meter reader came by on his usual day of the month to read our home’s electric meter. He told my mother that her hands sure looked worn out from the washboard she had been using. The meter reader then suggested to my mother that she buy an electric washing machine on a Central Maine Power layaway plan.”

That woman’s son was Harry Percival.[1] Harry’s parents made the washing machine purchase after the personal “soft sell” by the meter reader.

The lay-away (or deferred payment) plan made sense back then, since the $200 price tag for a washing machine in 1922 represented multiples of the typical residential customer’s annual electric bill. In 1922, $200 also represented 6% of a typical family’s $3,000 annual net income, vs. a $500 to $750 washing machine today representing only 1% to 1.5% of the net income of a family earning $50,000 annually.

Rethinking Customer Engagement

In marketing efforts for smart grid initiatives, there has been a tendency for some experts to talk about how we need to “change customer behaviors.” Such efforts are often accompanied by tailored messaging, via marketing programs, which use focus groups and market segmentation analysis of utility customers (e.g. based on surveys). In this marketing model, an implicit goal seems to be to not offend anybody. Elderly people are provided different smart grid product messages than Gen X’ers or Millennials. And in some cases you may have blue state or “green” customers being given more environmentally-centric messages, while red state or non-environmentalists being targeted with messages focused on cost savings.

In contrast to this “feelings based” or “politically correct” marketing approach, isn’t it much more compelling to think in terms of cool products and services that a lot of people will want? Consider how Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, each in their own different ways, did not create their Macs or PCs based on marketing surveys, or by using segmented messaging approaches. Beyond any of the above-mentioned artificial marketing strategies, their greatness came from their respective visions, which transcended “message-centric” marketing approaches. (Interestingly, saying that somebody is a “Mac person” or a “PC person” demonstrates the artificiality of the entire concept of market segmentation. These two labels are a way to “back-fill” a segmentation-based explanation after the fact.)

Looking to the 2020s

In preparing the utility industry for the next decade, aside from looking outside the box of “safe” segmentation approaches, we also need to ask “Why didn’t anybody?” types of questions, from the perspective of looking back at the 2020s, in the 2030s or 2040s.

In this regard, consider the lowly light bulb.

A “rear-view mirror” question we can ask is:

Think about how lighting systems generally control the number of lumens emitted from a lighting fixture, rather than controlling the level of lighting in the room, and then ask:

“For most of the last 100 years, why didn’t anybody develop lighting systems to control the actual overall level of light in the room? In other words, why didn’t anybody make the lighting system’s output vary as a function of the amount of sunlight coming into the room?”

Similarly, in the world of Demand Side Management and Energy Efficiency, other questions come to mind. Consider the current status of a lot of Behavioral Energy Efficiency programs, for example, with the following questions:

- Why are utilities trying to get a homeowner to “pay” more than a dollar’s worth of attention about their using around one dollar less of electricity during a peak event, instead of creating a repeatable process for a pre-set compelling and enjoyable experience?

- What portion of the target audience looks negatively at the energy-saving suggestion that people go out (e.g. to the movies or to dinner at a restaurant) during upcoming peak events to lower home consumption, due to their concerns such activities will yield a higher carbon footprint?

- Why can’t a utility’s set of options include DSM team groupings involving a “virtual home” consisting of all homes who are members of a group? For example, in one scenario the group could create a series of peak event rotating parties (like rotating dinner parties), where one location creates a very comfortable cool space and invites friends from the homes of all the group’s members over, so that in the aggregate the group saves power?

Conclusion

Utilities tend to talk to customers using dry utility terminology (e.g. compare our industry’s obscure terminology of “peak demand charge” to Uber’s more tangible term, “surge pricing”). Our emphasis on the monetary value of energy and demand needs to be replaced with an ecology of values based on comfort and connectedness. Fundamentally, we need to bring new value by enabling platforms that help architect beautiful new experiences relying on intelligent devices in the home.

Think about how short power outages create discomfort and disconnectedness, and how longer outages lead to the loss of fundamental things we hold dear in our lives. Why is it that most people do not associate a positive brand experience with the reliable service they get from their utility?

There is a branding opportunity here, to correct that.

[1] Harry E. Percival, Jr. was born in 1930 and passed away in 2001. Everyone who knew him will tell you what a great engineer he was, and how passionate he was about preserving the past and learning from it. After retirement from Central Maine Power, he fulfilled a life-long dream that lives on today with the museum he founded, the Wiscasset, Waterville & Farmington Railway Museum.