Whether power marketing administrations or investor owned, utilities face increasing pressure nowadays to keep costs down with limited budgets. Experts cope with how best to execute integrated vegetation management (IVM) to maintain safe clearances between vegetation and power lines. What has transpired in California over the last few years has only further magnified how a lack of appropriate vegetation management can adversely impact electrical reliability as well as public safety or property damage above and beyond the lessons learned from the 2003 East Coast blackout.

Expensive light detection and ranging (LiDAR), new technology and software commonly are promoted by vendors. However, utilities can leverage less expensive ways to operate an IVM program using low-tech tools to effectively reduce inherent risks and meet compliance.

The following best management practices have worked in Western Area Power Administration’s (WAPA) Desert Southwest region and comply with the North American Electric Reliability Corporation’s FAC-003-4 transmission vegetation management standard. This is not to suggest any of the practices described here are superior to others or apply to all utilities within their ecosystem footprints across North America. Instead, it is up to IVM experts to evaluate their assets and underlying ecosystems to make decisions that work best for their circumstances. Here is how WAPA manages vegetation in its service territory.

Annual Patrols

WAPA is a power marketing administration within the U.S. Department of Energy. It was formed through the Energy Organization Act of 1977, taking over from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation the management of 17,000 miles (27,359 miles) of transmission circuits across 14 states. Since then, WAPA has established its own internal guidelines for vegetation clearances and transmission line maintenance, environmental compliance and other related policies, known as WAPA Orders.

Per Requirement 6 (R6) of FAC-003-4, each utility is required to perform one annual patrol per applicable circuit every 12 months but no more than 18 months apart. Over the last 10 years, the use of LiDAR has increased in the electric utility industry. The problem with LiDAR is the cost associated with data collecting, processing and management. While LiDAR’s results are highly accurate, if the correct number of classifications are collected, they only represent a single snapshot in time.

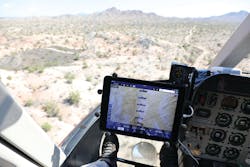

Instead, for a fraction of the cost, WAPA performs aerial patrols with transmission line maintenance (T-Lines) observers flying in helicopters, which satisfies FAC-003-4 R6. The helicopters are equipped with cameras that capture high-resolution imagery. Using a high-definition monitor, rights-of-way (ROW) evaluation or work list creation can be performed from the office instead of having to drive to the field to verify the information. Reports submitted by any party also can be evaluated when the span and circuit with the issue are known from the office.

As reported back in 2010, the most prevalent and best use of aerial patrols is the identification of imminent threat vegetation issues, but it needs to be taken in context. Only one plant can create a problem literally overnight in the Desert Southwest — the century plant, a member of the agave family.

Along the I-5 corridor in the western U.S., bamboo grows fast. In the Southeast, kudzu does. By shooting videos three times a year to show ROW conditions, in addition to the annual T-Lines ground patrol and the IVM manager’s review of roughly half of the transmission assets annually, the collected data provides redundancy in coverage, all at a fraction of what LiDAR costs.

Third-Party Inspectors

Another best management practice is to assign independent third-party inspectors to identify, validate and review IVM work. WAPA uses contract foresters from the Davey Resource Group Inc. (DRG) to perform these and other functions as well as for landowner notification, as required under WAPA Order 430.1C, especially when hazard trees need to be mitigated.

DRG contract foresters also have been tapped to verify recent vegetation-related reports on the ground or when WAPA cannot remove trees within the urban interphase. While the Desert Southwest does not have a preponderance of orchards or other agriculture settings, some almond, pistachio, date and citrus orchards still require periodic monitoring. DRG also provides quality reports for access issues as they are encountered.

One nuance with using contractors in a federal setting is they cannot act like a federal employee, including directing other contractors. Still, using them as a second set of eyes to verify or collect data is efficient and a value add.

The Data

When it comes to vegetation clearances, WAPA has five classifications of clearance per WAPA Order 450.3C. The ones IVM managers monitor most closely are the “D” maintenance clearance and “E” emergency clearance, per WAPA Order 450.3C. The “A,” “B” and “C” clearances usually are not used because of ground-to-conductor minimum engineering specifications at maximum sag.

WAPA currently uses CartoPac software to collect and store ROW data from its T-Lines observers’ inspections, while DRG records observations in its proprietary ROW Keeper. Archival information is stored in Maximo. However, all the data can be manipulated when converted to simple Excel spreadsheets.

By compiling and assembling spreadsheets with multiple tabs, data can be reviewed, verified and listed as mitigated. This provides evidential support to FAC-003-4 R1, R2 and R5. While WAPA continues to evaluate current and other software, a spreadsheet is still one of the simplest ways to store and manipulate data.

ROW Prescriptions

When looking at current high-voltage transmission ROW corridors across most utilities in North America, they usually are well defined by low-growing plant communities. The easement edge usually contains taller vegetation. Some utilities even possess easements that enable them to cut safe back lines or hazard-tree rights for off-ROW vegetation.

To gain this kind of appearance, mowing or mastication typically is prescribed. However, what if incompatible vegetation could be removed from ROW corridors while leaving well-established low-growing plants — all without having to mow or masticate the corridors? WAPA achieves this by cutting incompatible vegetation in its ROW corridors by hand, and it costs less than 20% that of outright mowing or masticating. This prescription retains ground structure that can be used by opportunistic neotropical migrants to nest and browse for ungulates or hiding/thermal cover along with rain intercept. It also reduces or removes fuel ladders, especially in the wire zone, to reduce the potential impact from wildfires, smoke or flame lengths — by lop and scattering the resulting woody debris within 12 inches (305 mm) of the ground. By comparison, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service requires slash to be left within 24 inches (610 mm) of the ground.

Because wildfire is an integral part of the western U.S. ecosystem, precluding wildfire is not WAPA’s goal. Instead, leaving woody debris and flashy fuels low to the ground is the standard, which keeps the flames low and relatively cool, preventing heat damage to hardware.

This ROW prescription also helps to protect both cultural sites and endangered species’ critical habitat. Because of the low impact this prescription provides to a given site and how much of the existing ROW plant structure is left intact, it is one of the best management practices WAPA can use.

Herbicide Treatments

Another best management practice just about all IVM managers agree on is the use of herbicides, at label rates, approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, whether applied to the cut stumps of those species receptive to the treatment or used as a follow-up application. Traditionally, this is a contracted service to the lowest bidder. Two contract herbicide sprayers provide bare ground treatment to WAPA for labor plus chemicals as part of its technician services contract with DRG.

This enables the two technicians to apply bare ground treatment twice per year and spend the remainder of the time either performing follow-up herbicide application within ROW or performing additional bare ground treatment around the radius of wooden structures along ROW. The cost savings for this is about 25% to 50% of the normal wholesale contracting for these services.

These are just some of the best management practices IVM managers can use to possibly accomplish their objectives at reduced costs. In a perfect world, where funding is unlimited, new technology can help to do jobs better. However, in reality, funding is limited and IVM managers need to find any opportunity to stretch dollars to cover what is needed to not only comply with FAC-003-4 but, in some cases, reduce the fuel loading on ROW.