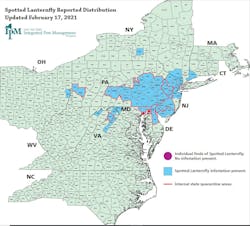

In 2021, the word quarantine has developed a special form of detestability in the American lexicon, but the quarantine restrictions around spotted lanternfly should not be ignored: they can affect right-of-way (ROW) managers’ productivity on the job and their quality of life at home. Spotted lanternfly (SLF), Lycorma delicatula, is an invasive planthopper from Asia that was first discovered in Berks County, Pennsylvania, in 2014 and has quickly spread to at least eight surrounding states. This insect poses a significant threat to grapes and other crop plants as well as to Americans’ enjoyment of outdoor spaces. While SLF may not have a direct impact on the ROWs we manage, this conspicuous insect has already had severe impacts on transmission and distribution utility vegetation management (UVM) productivity and agriculture adjacent to ROWs.

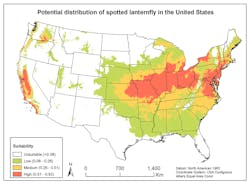

The insect is a notorious hitchhiker. Though SLF has not made it west of the Mississippi yet, California has already categorized it as an A-rated pest because an infestation would be a major blow to the fourth largest wine producer in the world. Spotted lanternfly’s prodigious appetite for valuable crop plants, locust-like swarming behavior, ability to travel via egg masses on virtually any surface, and prolific reproductive rate make it a serious threat to the many American states it is capable of colonizing.

Our role as vegetation managers makes us uniquely qualified to monitor and prepare our communities for new pests, and the nature of UVM and utility work means our vehicles and equipment must be inspected every time they move in areas where SLF quarantines are present. Finally, our presence as residents in the communities we serve means that we may have a personal stake in the problem. According to Brian Walsh, a researcher with Penn State Extension in Berks County, there are areas in the heart of Pennsylvania’s infestation where, come the fall, “you can’t drink a beer and grill without SLF landing on your grill and/or your beer.”

A Pervasive Plant Stressor

Spotted lanternfly is a planthopper, which means it feeds on plants with piercing, sucking mouthparts. It feeds upon a large variety of plants but tends to focus on a handful of preferred hosts such as rose, walnut, birch, willow, sumac and maple. Its two favorites are tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima) and grape (Vitis spp.).

Spotted lanternfly is a plant stressor, weakening plants and making them more susceptible to other insect and disease vectors, but it has been shown to kill grape and tree-of-heaven plants outright in particularly intense infestations. The direct economic impact to Pennsylvania agriculture in the quarantined zones is already estimated at $13.1 million.

The insect does not bite or sting people or animals and does not do direct damage to structures. When SLF feeds on a plant, any sap the insect does not use it expels as a sugary substance called honeydew, which then collects on lower parts of the plant and anything beneath it. In large infestations, honeydew can coat cars, plants, houses, lawn furniture, and anything else beneath the trees SLF is feeding on. Honeydew’s moisture and sugar content attract other insects such as yellow jackets and make it a prime growth medium for black sooty mold. In areas where SLF is abundant, many property owners complain that they cannot enjoy their outdoor spaces in the late summer and fall due to the raining honeydew, pungent odor of fermenting sap, prolific growth of black sooty mold and presence of wasps – not to mention the abundance of SLF itself, a rather large insect.

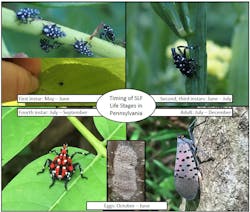

Spotted lanternfly completes one life cycle per year. After spring egg hatch in May and June, it goes through four adolescent nymphal stages, referred to as instars, before molting into its adult form as early as July and as late as September. Adults are generally present from July through December, with the most voracious feeding and swarming activity occurring in the fall. Spotted lanternfly adults are easily recognizable by their 1-in. length and pinkish-tan-colored wings with black spots. When seen in flight, an adult’s wingspan is about two inches, and red inner wings and yellow markings on the abdomen may be glimpsed. Nymphs can be much harder to spot: they are only about a quarter inch in length when newly hatched and look like black ticks with white spots. As they mature, they maintain their color pattern through the third instar but grow to a half inch or longer. Fourth instar nymphs are black and red with white spots and up to three-quarters of an inch long. Only adults have wings.

Adults lay eggs from September through about December, or until sufficient cold kills off the adults. Spotted lanternfly egg masses are about one inch long and contain 30 to 50 eggs. Egg masses are usually laid with a protective waxy coating, almost white at first, which cracks and fades to gray or brown as the winter progresses. Occasionally, egg masses will be partially or fully uncovered, revealing four to seven vertical rows of eggs. Though egg masses may be laid on almost any smooth surface including vehicles, tools and equipment, most are laid 10 ft or higher up on trees. When SLF egg masses are found, they should be destroyed and, if outside a quarantined zone, reported to the local state environmental protection agency.

Quarantine and Permit Requirements

Spotted lanternfly quarantines were instituted because the insect is a threat to agriculture and forestry and a nuisance that threatens residents’ enjoyment of the outdoors. Quarantines exist in six American states as of March 2021: Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia. Associated permits are reciprocal between states, and each state’s SLF permit requirements are essentially identical. Quarantines may slow the spread of SLF, which will allow the scientific community time to investigate measures to control or eliminate it. The containment, monitoring and documentation measures dictated by the quarantine are also necessary to ensure that trade can continue within the United States and abroad from areas where infestations are present.

The quarantine works by restricting the movement of SLF and items that can harbor it, therefore isolating breeding populations and preventing humans from accelerating their spread. Utilities and their contractors, with large vehicles sometimes moving across state lines, have the potential to spread SLF and are subject to quarantine rules. Regulated articles within a quarantined zone must be inspected for SLF and their egg masses before they are moved, even if the movement stays within the respective quarantined zone. Regulated articles include any life stage of SLF, plants, plant waste, vehicles and essentially any item stored outdoors: tools, utility poles, transformers, lawn furniture, pallets, trailers and so on. If an item must be stored outside, it may be covered securely with a tarp or other covering that will prevent SLF from getting to it prior to movement. Inspections do not need to occur during the months in winter and early spring that SLF is not moving, but a thorough inspection of regulated articles must take place to remove egg masses during this time, before eggs hatch in spring. Inspecting for eggs throughout the egg laying season is the best practice, as freshly laid eggs are brighter and usually easier to spot.

All businesses, agencies and organizations — agricultural and non-agricultural — that move regulated articles within or out of quarantined areas must have a permit and comply with quarantine regulations. The only exceptions are businesses and entities that move regulated articles through quarantined areas (both arrival and destination outside the quarantine) and only stop for refueling, traffic and emergencies. There are potential civil and criminal penalties for businesses and entities failing to comply with the permit regulations.

The business or entity seeking permits must have at least one employee become a designated trainer by taking an online training course through their local State Extension office or State Department of Agriculture. That trainer is then responsible for training any personnel responsible for moving and inspecting regulated articles, and for issuing a permit to each trained employee. The business or entity must keep training records for all trained employees, including an acknowledgement that the employee understands his or her responsibilities regarding preventing the spread of SLF. Each permitted employee must carry the permit on their respective vehicle or conveyance. The business or entity’s permit is renewed annually, but the trainer only needs to take the course once.

UVM and Utility Operation Impacts and BMPs

Utilities and their contractors operating in quarantined areas have already lost many hours to SLF inspections and record keeping. Most of the burden lies in inspecting vehicles, tools and other equipment stored outdoors in quarantined zones prior to movement at the start of the day, before moving between job sites within or to outside a quarantined area, and before heading back to the yard at the end of the day.

To save time, drivers should work SLF inspections into their daily safety walkarounds. Outside crews coming into a quarantined area for storm restoration or other emergency work should be briefed on SLF restrictions and inspection requirements prior to their arrival. Some other best practices for operational hygiene in SLF infested areas include avoiding parking vehicles or placing equipment near trees, parking vehicles close to job sites in quarantined areas where practical, never leaving parked vehicle windows, trunks, or tool bins open, and storing vehicles and equipment indoors whenever possible. Plant material that is not chipped smaller than one inch in each of two dimensions must be inspected prior to movement from within a quarantined zone. Drivers should scan the interior of their vehicle prior to movement to avoid hitchhikers.

Understanding what life stages are present at a given time will help crew members know what to look for during inspections and keep an eye out for the insect during the workday. If any member of a crew notices SLF while working, she or he should alert the rest of the crew to be on the lookout, and all tools must be inspected before being loaded back onto the truck. In areas of high populations or swarming, crew members may want to tuck pants into socks and shirts into pants; SLF has little fear of humans and is known for climbing up essentially any vertical surface it can get a grip on. Crew members should also search their own clothing for SLF before leaving an infested area. Documentation must be kept of all inspections as well as control measures taken if SLF is found. The template for inspections is up to the business or entity holding the permit, provided it can show it did its best to prevent the spread of the pest.

Proactive Monitoring and Management

UVM workers are well suited to contributing to monitoring efforts for SLF. Electric infrastructure exists throughout the United States and crosses in and out of quarantined zones. Quarantine regulations will require a multitude of foresters, contractors, line workers, engineers and other field employees to be trained on SLF identification and quarantine boundaries. As utility workers and contractors come into compliance with SLF permit regulations, they may contribute to SLF control above the permit requirements by keeping an eye out for SLF outside of quarantined zones. Utilities, contractors, local governments and other stakeholders outside the quarantines should also be encouraged to assist in monitoring. Every satellite population that gets reported to the state is another opportunity to slow the insect’s progression and prevent new infestations. If possible, please take a picture and record the location when reporting an SLF sighting outside a quarantined zone.

ROW vegetation management activities can also help with SLF management directly, especially in proximity to grapes and other agriculture. When asked for recommendations for how UVM operations can assist with SLF control, Emelie Swackhamer, an educator with Penn State Extension, had this to say: “If possible, eliminate large stands of Ailanthus altissima [tree-of-heaven], especially near vineyards, transportation corridors, commercial sites that ship products, and residential areas. Although research has shown that SLF does not require Ailanthus altissima, it is a highly favored host tree. If Ailanthus is abundant, extremely high populations of SLF can occur and they will move to adjacent areas, especially as adults.”

She also suggested controlling Asian bittersweet and other invasive plants that SLF prefers. ROW managers practic- ing integrated vegetation management typically control for invasive plants such as tree-of-heaven and manage their ROWs to favor low-growing, early successional habitat, which may limit ROW populations of SLF.

Looking Ahead

Spotted lanternfly is here to stay, but control efforts are ongoing and improving. Chemical and biological controls are already in use in agriculture and on private properties. Penn State Extension and similar agencies have a wealth of knowledge for industries and home-owners alike, including a web page on how to make a homemade “circle trap” to capture SLF at home.

Walsh is working on a pilot project that is being developed between Penn State and FirstEnergy where utility poles are fitted with SLF traps to assist in monitoring. The United States Department of Agriculture is working diligently to limit SLF’s spread through travel corridors and shipping lines. State natural resource managers from areas outside the quarantined zones are putting out educational materials to urge local residents to be on the lookout for SLF. Researchers from the United States and abroad are investigating chemical, cultural and biological control methods to combat the pest. California is rigorously inspecting imports to prevent SLF from reaching the wine valley. It is essential that we all do our part to limit the spread of SLF.

Editor’s Note: Thank you to Emelie Swackhamer & Brian Walsh with Penn State Extension, Paul Kurtz with New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, Penn State Extension, Pennsylvania State University and Cornell CALS/New York State Integrated Pest Management for providing the information for this article.

Kieran Hunt is municipal manager with Asplundh Technical Services and works with Asplundh’s field operations to improve and expand municipal and roadside vegetation management programs. His background is in municipal and utility vegetation management, inventory, and work planning. He is an ISA certified arborist utility specialist and a New Jersey Licensed Tree Expert and has a B.S. in ecology from Rutgers University.