Wildland fires are happening across the United States. According to a June 2022 T&D World article by ACRT Services Senior Manager Bob Urban highlighting the sheer amount of damage these fires can produce, 2021 saw nearly 59,000 wildfires burn more than 7.1 million acres (2.8 million hectares), and 2020 saw the highest number of acres burned — 10.1 million (4.1 million hectares) — over the preceding five-year period.

With the volume of land impacted by wildland fires, it is natural to look for environmentally friendly solutions. This is where a basic understanding of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and cultural burning can become an asset.

Vegetation Management Practices

Vegetation management practices are always evolving. Early in America, indigenous communities managed their ancestral lands in a variety of ways. For thousands of years prior to colonization, fire was integral to many Indigenous people’s way of life. Indigenous people on what is now called Turtle Island in North America used fire to travel, manage the land for cultivation of fauna (animal life) and flora (plant life), hunt game and more. Fire was a tool that promoted ecological diversity and reduced the risk of catastrophic wildfires.

TEK is defined by the National Park Service as the ongoing accumulation of knowledge, practice and belief about relationships between living beings in a specific ecosystem that is acquired by Indigenous people over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment, handed down through generations and used for life-sustaining ways. This knowledge includes the relationships between people, plants, animals, natural phenomena, landscapes and the timing of events for activities such as hunting, fishing, trapping, agriculture and forestry.

TEK encompasses the worldview of a people, including ecology, spirituality, human and animal relationships, and more. In stark contrast to Western society science, TEK uses more holistic and inclusive beliefs.

Cultural Burning

Many indigenous communities and tribes use traditional cultural burning practices with TEK to cultivate their lands. This practice typically uses a small, controlled fire to provide a needed result monitored by a tribal burn boss or traditional practitioner of fire. The U.S. Forest Service has seen the value of these traditional fires and adopted some of the uses in clearing ladder fuels from heavily forested areas at risk of a catastrophic fire, and many other entities are taking notice.

Fire Intensities

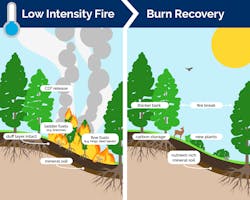

Low-intensity fire cultural burning is best in these: cool, moist and low wind speeds. However, depending on the specific vegetation to be targeted for cultivation, it may occur in various months. One of the most critical aspects is the fuel load, which needs to be low. The fire should be lit on a high incline to force the fire to work slowly downhill, preventing it from fuel loading uphill and blowing up into a monstrous, uncontrollable fire — like the Hermits Peak Fire in New Mexico, set by the U.S. Forest Service, that escaped containment and caused millions of dollars in damages.

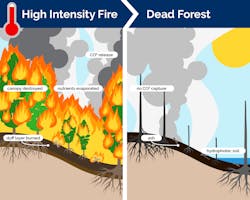

High-intensity fires differ because of the damage the fire does, wiping out the duff and creating hydrophobic soil that can create erosion issues, mudslides and flash flooding issues. Indigenous peoples knew this and, thus, managed their lands with TEK, passing down the traditional knowledge from many generations to today.

Currently, in the Central Valley of California, there is a resurgence in TEK usage and cultural burning, thanks to North Fork Mono Tribal Elder Ron Goode, who has decades of cultural burning experience, and the next generation of tribal burn bosses like Ray Gutierrez, a Wuksachi tribal member, who has advanced degrees in forest ecology. Gutierrez is merging his traditional knowledge with academia to help cultivate gathering materials, such as redbud and sourberry. According to Mono elders, sourberry sticks used for basket making need to be cultivated with fire; otherwise, the plant grows up bushy and the shoots grow crooked, unsuitable for basketry. Mono Elder Julie Dick Tex explained that “a gentle fire clears the brush, regenerates the plant, and coaxes new shoots straight toward the sun.”

Wildfire Education

Students in Humboldt County, California, are being introduced to Native American science, technology, engineering, art and math (STEAM) and studying TEK. As part of that, they are learning about cultural burning. A press release in the North Coast Journal shared the curriculum for elementary and middle school-aged students, which included teaching how “fighting fire with fire helps prevent wildfires.”

Oregon State University’s college of forestry is studying TEK and is home to a traditional ecological knowledge lab. Currently, the students are conducting two studies: A three-year Pacific Northwest ethnobotany, seed collection and tribal conservation corps ecocultural restoration pilot project, and a five-year project to expand on an interdisciplinary ethnobotany and TEK pilot project initiated by Dr. Cristina Eisenberg in 2019.

Wildfire Education

As Bob Urban noted in his fire safety T&D World article, “Everyone is stewards of the land they manage and work on, and a living fire plan is one of the best ways to ensure it continues to thrive for years to come.”

When drafting vegetation management and wildland fire safety plans, it is beneficial to keep TEK top of mind. One might ask: What does TEK truly mean for vegetation management? A well-balanced approach to the future of the electric utility industry is the answer. By using indigenous best practices and Western science — acculturating the best of both — the industry will become more resilient and foster mutual respect for tribal and non-tribal knowledge. In a University of California, Davis article by Kat Kerlin, “Rethinking Wildfire,” cultural burning and TEK can be summed up with one quote by Mono Elder Ron Goode, “There’s a difference between cultural burning and just setting fire on the land. We use fire as a tool.”

M.K. Youngblood serves as the safety manager and tribal liaison at ACRT Pacific. He has more than 30 years of public service and first-responder experience with core proficiency in American Indian law, American Indian culture and disaster cleanup. Youngblood also serves as a certified instructor for the U.S. DOE (National Nuclear Security Administration and Center for Radiological Nuclear Training), U.S. Emergency Management Institute and Center for Domestic Preparedness. He has earned his California Naturalist designation from the University of California, Davis and serves as the tribal historic preservation officer for the Haslett Basin Holkama Mono Nation in Fresno, California.