In recent years, utility vegetation management (UVM) has become a more urgent business. The reasons are not simple, but most would agree a vast majority of electric consumers expect reliable service 24/7. Several driving forces surrounding the consumption of electricity have resulted in less tolerance for electric service interruptions. An increased number of electric consumers, a greater focus on electronic communications and a myriad of other electrical needs make electricity far more ubiquitous than in previous decades. In fact, uninterrupted electric grid function is becoming more of a legislated right than in the past.

This shift has long-range implications for the design and maintenance of electric delivery systems. In particular, new expectations for electric distribution systems imply UVM programs must be longer range, more comprehensive and more results based than what has been considered reasonable in the past. It is no longer sufficient to erect infrastructure that can withstand typical or normal environmental conditions. Today’s grid must be resilient and be able to heal quickly from the forces of nature, especially given the new variability of climate change.

Response to Extreme Weather Events

The mandate for electric reliability has resulted in new rules that address the risk of outages occurring and rules that require utilities to respond better when forces of nature impact their system operations. New regulations are appearing in states where multiple weather events have made national news by causing severe damage to electrical infrastructure. In particular, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Maryland and West Virginia are adopting game-changing vegetation management rules aimed at reducing interruptions and the duration of interruptions. The long-term success of these initiatives is mostly unknown, but the extent of required UVM work and the resources available for the work have increased significantly.

There is a commonality to the way in which each state is evolving its UVM regulations. First, storms occur and cause extraordinary damage to the electric grid. Customers complain that the widespread power outages are a hardship and the utility should be able to do a better job. Then, the utility commission commences a fact-finding proceeding and determines there should be a new regulation for vegetation management.

Although the precipitating events are similar and result in increased UVM, the new state regulations are not necessarily alike. Each state is developing unique regulations and performance expectations. The regulations address a wide swath of UVM activities, including annual reporting, reliability measurements, cycle lengths, clearance distances, restoration time limits, mutual-aid agreements, communications protocols, adequate personnel and adequate routine maintenance. Each state’s regulation has unique characteristics.

To complicate matters, mergers have united utilities from different states with an expressed objective to bring economies of scale and efficiencies of management to benefit the ratepayers. For UVM, the result is multiple state regulations applied to the same utility. The efficiencies gained from merging UVM programs are offset by multiple complex regulatory requirements.

The new UVM rules provide the customer with improved reliability and other important benefits. For some utilities, more effective UVM rules can bring constructive change and solutions to UVM problems that have persisted for decades. For others, the new risks involving changing ecologies and cultural preferences can be mitigated successfully through regulations that address the concerns of the utility.

Even though the new rules are precipitated by customers who are dissatisfied with electrical interruptions caused by storms, some customers quickly forget the inconvenience and seek to prevent the utility from taking proactive measures to make their distribution systems more resilient to storms. Eventually, experience will reveal the more successful regulations. If the best regulations are allowed to prevail, they could become standardized for many or all states, and UVM for all utilities could be improved to meet a universal standard of care and specific regional needs.

Connecticut’s New UVM Regulations

An example of a comprehensive change in regulations is Public Act No. 13-298 of the Connecticut Legislature, signed into law by the governor on July 8, 2013. Not only does this piece of legislation change the obligations and rights of utilities in Connecticut with regard to vegetation management, but it also restructures the way in which utilities are regulated. Section 60, which is three-and-a-half pages of the 93-page law titled “An Act Concerning Implementation of Connecticut’s Comprehensive Energy Strategy and Various Revisions to the Energy Statutes,” replaces previous vegetation management regulations.

The new UVM regulation (Section 16-234) created a utility protection zone (UPZ) and changed the requirement for adjoining property owner consent to abutting property owner notification. The UPZ is defined as “any rectangular area extending horizontally for a distance of 8 ft [2.4 m] from any outermost electrical conductor or wire installed from pole to pole and vertically from the ground to the sky.” Abutters must be notified at least 15 days before the commencement of any vegetation management, defined as the “pruning or removal of trees or other vegetation that pose a risk to the reliability of the utility infrastructure.”

Notification can be with a door hanger, face to face or via U.S. mail. Notice is not required when the municipal tree warden authorizes the work on a hazardous tree within the UPZ, within the public right-of-way or when a tree is “in direct contact with an energized electrical conductor or has visible signs of burning.” If the abutting property owner does not object within 10 days of receiving notice of proposed work, the utility can prune or remove incompatible vegetation in the UPZ.

Connecticut utilities are spending or planning to spend more than triple their previous budgets to clear and remove trees in the UPZ. When the property owner refuses the proposed work, a two-stage review occurs involving the tree warden and then, if necessary, the Public Utility Regulatory Authority (PURA). Where it sees fit, PURA is empowered to decide in favor of public convenience and necessity.

Public resistance has led to recent congressional revisions to Section 3 of 16-234, which changes how the UPZ is managed. The May 7, 2014, revision states that it is the utility’s responsibility to prove the necessity of removing a tree. Property owners’ consent is required for removals on their property, and they may refuse for any reason to allow tree work in the public right-of-way. If a tree refused for removal or pruning falls into the lines later, property owners will not bear financial responsibility for the damages. Tree wardens and the commission must settle disputes. In contrast, California utilities have the right to shut off the power on customers who refuse and obstruct planned vegetation management work that is required by law.

The UPZ does not mandate the utility to perform specific UVM activities in compliance with preset clearance distances, but it does provide prescriptive rights that few states have allowed the utility industry.

However, Connecticut utilities did not receive new UVM rights without incentives to exercise them. A year before the UPZ was crafted for Section 60 of Public Act No. 13-298, the Connecticut Legislature responded to the will of the electric consumer when it passed Public Act No. 12-148, “An Act Enhancing Emergency Preparedness and Response.” In this act, PURA is authorized to penalize utilities not fully prepared to respond to storms, which includes vegetation management activities.

This negative incentive is similar, at least in the intended modification of behavior, to rules in other Eastern states. For example, a similar law in Massachusetts not only gives the state the right to penalize utilities for inadequately responding to widespread outages, but it also gives the state the right to take possession of or mandate specific actions. A utility that has not acted reasonably to prevent outages from storms and has not responded sufficiently to restore electricity to its customers is subject to penalties under this Massachusetts regulation.

Similarly, in Connecticut, each electric distribution utility is required to meet performance standards for any event that exceeds 10% of the customer base for longer than 48 hours. Failure to comply can result in nonrecoverable penalties up to 2.5% of the annual electric distribution revenues. This is the same penalty as in Massachusetts. The performance standards apply to a range of activities that, if implemented, can decrease the impact of storms, even catastrophic storms.

Other Regulatory Initiatives

Other Eastern states are in the process of crafting new UVM laws to protect their citizens from the inconveniences and dangerous hazards caused by widespread electric interruption and damaged overhead facilities.

In Maryland, a new rule requires a ground-to-sky clearance for high-voltage distribution lines.

West Virginia has been studying ways to address the challenges of reducing the massive damage of a storm’s impact on distribution systems in areas of rugged mountainous terrain, high tree density and low customer density.

According to NJ Spotlight, an online news service, the Board of Public Utilities in New Jersey recently “issued an order to begin a process among utilities, local officials and forestry experts to determine what steps are needed to prevent widespread outages caused by trees or branches falling on power lines.”

This scenario is likely to be repeated in many more states, and utilities need to pay attention to how policy makers are attempting to solve the century-old problem of trees and power lines in this new era.

William Porter ([email protected]) is director of consulting services at CN Utility Consulting, a company that offers utility vegetation management consulting and field services. Porter has more than 20 years of experience in the utility vegetation management industry and has led consulting projects and benchmark studies throughout the U.S. and Canada. He has focused his research on legal, program development and comparative studies.

Sidebar: Tree Assessments: A Critical Component of Outage Risk Reduction

In 2012, a new vegetation management standard, American National Standards Institute (ANSI) A300 Part 9, was published and adopted by the utility vegetation management industry. Trees or tree parts falling into conductors cause the majority of outages. One utility has estimated there are more than 10 times as many trees that can cause outages than are typically managed by line clearance.

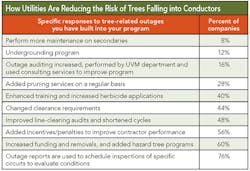

Seventy-one percent of tree-related outages are fall-in, and 41% of utilities have a hazard tree program, as reported to CN Utility Consulting. Eighty-one percent of utilities report they remove healthy trees that have multiple leaders with included bark.

By using the level one method of the A300 Part 9, utilities could eliminate the most obvious trees that have a higher probability of causing an outage. Thirty-six percent of utilities stated they remove healthy trees that pose a risk to feeder lines, and 60% of utilities have increased the number of removals in the last five years.