Utilities have long experience in managing risks. Prior to April 2013, most utilities thought those risks were well known; topics like theft, vandalism and workplace violence were high on most security agendas. But a team of still-unknown snipers changed all that when they opened fire on Pacific Gas & Electric’s (PG&E’s) Metcalf substation in San Jose, California, U.S. Though the shooters’ speculated objective of causing a widespread power outage was unsuccessful, the incident ushered utilities into a changing and much more complex threat and risk dynamic.

With the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s approval of the North American Electric Reliability Corporation’s critical infrastructure protection standard for physical security measures (CIP-014) on Nov. 20, 2014, utilities have entered into an era many could not have imagined prior to the events in San Jose. They face new risks that will require them to identify and look at vulnerabilities in a completely new way. Those familiar with CIP-014 know once a utility’s risk assessment has identified whether damage to its transmission assets could lead to widespread instability, uncontrolled separation or cascading within an interconnection, the vulnerability evaluation of requirement four (R4) and security plan work of requirement 5 (R5) compliance begins.

Security Plan

The R4 process begins with a potential threat and vulnerability evaluation. It is important for a utility to understand that threat information, by its nature, is perishable. Threats can change faster than regulations can be drafted and approved to address them. It reminds one of the old adage: “You show me a 10-foot wall; I will show you an 11-foot ladder.”

The best way for a utility to protect its assets is to stay on top of threat information. Gathering threat information regarding specific assets and locations should be an active task completed on a regular schedule by the corporate security professionals within an organization. This enables the organization to be proactive, and not reactive, to its specific threat environment. Additionally, R4 creates a framework for the site vulnerability evaluation based on known and documented threat information and the history of attacks on similar facilities. This documentation includes evaluating

frequency, proximity and severity of past events.

The events of San Jose would lead most observers to conclude utilities must simply protect critical assets against small-arms fire. However, the reality is many utilities are now evaluating nontraditional threats and more complex risks derived from those threats, including those from direct fire weapons such as light anti-armor weapons or rocket-propelled grenades, improvised explosive devices, and vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs). These evaluations have not been limited only to CIP-014 sites. Many utilities are now evaluating vulnerabilities of utility-critical assets to these threat and risk scenarios to better position themselves within a potential changing threat dynamic.

Threat Evaluation

Evaluating these complex threats at each site puts the utility in a proactive versus reactive state. Evaluating threats that may be defined as emerging enables the organization to better understand its current security posture based on a wide range of risks that go well beyond the narrow range of risks that may have been presumed from local experience. As an example, many utilities agree the probability of VBIEDs within the U.S. may be low, but the mitigation methods for this type of an event can be reasonably employed, require little operation and maintenance costs, and mitigate other threats and risks such as forced entry to a given site.

When utilities are evaluating sites within a broader context of more complex threats and risks, it is very important to frame these based on actionable threat information and information about previous events. Without framing, or defining, the threats and risks, the evaluation will be very open ended with findings that can be called into question.

Mitigation Options

Once the utility completes its site vulnerability evaluation, it must begin the process of identifying mitigation options. When thinking of such options, most think of cameras, access control and intrusion-detection devices. While these are important elements of most security programs, as they can certainly serve as a force multiplier, other pieces can cost less and be even more important.

Policies and procedures are the guidelines and expectations that guide an organization. The same principles apply to security. A utility can erect expensive high-end cameras, but if the operators do not know how to use them and do not have appropriate guidelines to initiate a response, the investment is wasted.

When seeking to identify mitigation options, it is wise to look at the entire security operation. Items such as badge in/badge out policies for critical locations or programs that require operators to tour the work site prior to initiating work, identify situations as out of the norm and report those findings are all examples of measures that can significantly improve the security posture of a site.

It is prudent for utilities to first identify those solutions that are policy and procedural as they are far less costly to implement and maintain. After vulnerabilities are identified that cannot be addressed through policies and procedures or that need to be strengthened, it is time to ask this question: “What physical measures can be put in place?”

Flexible Security Strategies

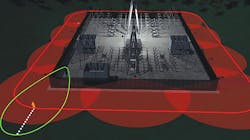

The potential changing threat dynamic utilities face generally requires serious consideration of new electronic means of alarm and assessment. Traditionally, utilities focused much of these efforts on the inside of the facility perimeter. The thought was that simply identifying the presence of an intruder would allow sufficient time to determine a response. While intruder identification is still the core of a utility’s security plan, the need for much earlier detection is becoming more prevalent.

The ability to detect a potential adversary well away from the perimeter enables earlier assessment by the security operations center and creates time for an effective response. There are many options for external detection from thermal cameras to vibration detection to ground-based radar. The solution for a given site is driven by site constraints such as property lines, environmental considerations and the terrain.

At one utility, for example, the risk profile of various high-voltage substations required security measures focused heavily on deterrence in addition to intruder detection and delay. The importance of power reliability to the area served by this utility’s power infrastructure required installation of hardened perimeters built after extensive surveys of sight lines, adversary characteristics and clearances at each facility.

Though threat scenarios are almost always unique to each utility, the best security strategies are always built around the philosophy of deter, detect and delay, and are commensurate with the corporate security strategy. Add to that the important elements of the careful assessment of risks, investment in secure communications and detailed response plans. Regulatory agencies are generally supportive of security strategies that are flexible enough to escalate or de-escalate rapidly in response to known threat scenarios and support operational tempo.

No Battle As Sun Tzu wrote in The Art of War thousands of years ago: “The greatest victory is that which requires no battle.”

Preparation for threats faced by utilities today requires a level of diligence never before required. But with proper planning and proactive investment, utilities will meet these challenges.

Robert J. Hope ([email protected]) is a senior project manager for Burns & McDonnell’s global security services group, responsible for helping organizations to identify security threats, and evaluate and mitigate risks by implanting sound security measures. With more than 15 years of experience in overall security operations, he specializes in the design, delivery, training and operation of security operation centers and speaks regularly on security topics. He is a certified project professional and an associate business continuity professional.