Partnership Produces Environmental Benefits

Successful implementation of integrated vegetation management (IVM) requires cooperation with stakeholders along rights-of-way (ROWs). A stakeholder is anyone with an interest in how ROWs are managed. National Grid, an electric utility with facilities in five Northeast states, and one of its notable stakeholders, the Massachusetts Audubon Society (Mass Audubon), formed a partnership to showcase how IVM can benefit this stakeholder and the environment.

How the Partnership Began

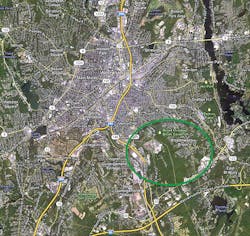

In the 1960s, National Grid’s predecessor company, New England Power Co. (NEP), acquired land for a power line in Worcester, Massachusetts, U.S. The landlocked wooded land was of such low value the utility bought the ROW and parcels of land it traversed, some 150 acres (61 hectares). As residential development occurred in the 1960s and 1970s, this land and other abutting properties became a green island, or accidental wilderness, within Worcester.

With a population of approximately 200,000, Worcester is the second-largest city in the six New England states. It is also the largest city served by National Grid in New England. National Grid and its retail electric affiliates serve approximately 3.1 million electric customers in Massachusetts, Rhode Island and New York.

The Mass Audubon is one of the largest and most influential environmental nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Massachusetts. It owns and manages more than 50 wildlife sanctuaries across the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. In the 1980s, the Mass Audubon established a resource office in Worcester and began looking for opportunities to develop an urban wildlife sanctuary and environmental education center. Review of remaining open space in the city revealed the green island that included the NEP power line ROW.

Following negotiations, a lease agreement between Mass Audubon and NEP was signed in 1991. This agreement allowed the Mass Audubon to incorporate the power line corridor and surrounding land owned by NEP into the sanctuary. Mass Audubon established Broad Meadow Brook Conservation Center and Wildlife Sanctuary in 1989. The keystone parcel of land to establish Broad Meadow was the 150 acres owned by NEP.

Over the past two decades, the sanctuary has grown to 430 acres (174 hectares) of conservation land, of which 172 is owned by or subject to conservation restriction held by Mass Audubon. The remaining acreage is owned by various private (including National Grid) and public entities, and collaboratively managed for conservation purposes by Mass Audubon. In 2011, the agreement between NEP and Mass Audubon was extended for another 20 years.

From the beginning, all entities recognized the power line corridor represented unique opportunities for habitat management at Broad Meadow. The partnership agreement with NEP does not restrict vegetation management of the corridor, maintenance to the electric transmission line or upgrades to the line. As Mass Audubon moved forward with management of natural resources on Broad Meadow, NEP worked to integrate vegetation management practices complementary to Mass Audubon’s habitat management objectives. Selective herbicide application within an integrated framework continued within the sanctuary.

IVM at National Grid

Herbicides became widely available as a vegetation management tool after World War II. In the 1950s, NEP, like many electric utilities, used aerial application techniques on thousands of miles of ROW. Gradually, aerial applications gave way to ground-based application. In the 1950s and 1960s, several researchers became interested in the use of herbicides to manage ROW.

Frank Egler was an early advocate for the use of selective herbicides and selective application techniques to control undesirable plants and promote the establishment of desirable plants — low-growing shrubs, grasses and forbes. Egler mostly viewed the practices and results of herbicide use by electric and roadway vegetation managers as a missed opportunity. He thought the utilities’ emphasis on vegetation control overlooked the benefits that could be achieved by using herbicides selectively to promote a low-growing plant community. Bramble and Byrnes began to research the effects of herbicide use in the early 1950s, as well.

Ground applications provided the opportunity for NEP to transform its vegetation management program to selective management in the 1970s. Over time, application methods evolved to where most treatments were applied using handheld backpack equipment. During this time period, many studies focused on the benefits to the ROW plant community, leading to an increased realization that the biological control exerted by the low-growing plant community provided a stable environment and reduced the frequency and cost of selective applications.

During the late 1960s and 1970s, public opposition to herbicides led to many electric utilities restricting or abandoning herbicide use in their vegetation management programs. Environmental impacts of indiscriminate pesticide use became controversial. Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring galvanized the public and the nascent environmental movement to advocate for reduced use or to ban the use of certain pesticides. Clearly, use of herbicides by electric utilities would not be tolerated by the public and regulators for long unless integrated methods of pest (vegetation) control were adopted.

It is worth noting that Carson referred to Egler’s advocacy for selective use of herbicides and cited utility use of herbicides as a positive example of sound pesticide use. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began advocating for the use of integrated pest management (IPM) methods of pest control during this time period.

In the early 1990s, the concepts of IPM became the backbone for ROW vegetation management techniques employed by many electric utilities, primarily in the Northeast. IPM evolved into IVM as industry vegetation managers incorporated IPM principles. Kevin McLoughlin, a former system forester at New York Power Authority, was one of the first authors to use the term IVM. Today, the EPA publishes a fact sheet on electric utility IVM.

A formal framework for IVM was published by Chris Nowak and Ben Ballard in 2005. All core elements of IPM were included in the IVM framework. At about the same time, American National Standards Institute (ANSI) A300 was adopted by the industry. A300 defined IVM as a system of managing plant communities in which managers set objectives; identify compatible and incompatible vegetation; define action thresholds; and evaluate, select and implement the most appropriate control methods to achieve those objectives.

Nowak and Ballard and the International Society of Arboriculture (ISA) best management practices (BMPs) added the monitor treatments and quality-assurance elements widely used today. Together, these core elements comprise a systematic approach to vegetation management. Egler would be pleased.

A core element of IVM is biological control of the undesirable vegetation — in this case, tall-growing tree species. Many authors have documented how the impact of the selective removal of undesirable trees, and resulting establishment of low-growing desirable plants, leads to a stable plant community that exerts biological control through competition for light and physical access to mineral soil needed for seed germination. Other authors also have demonstrated the allelopathic attributes of certain shrub and herbaceous plants that provide biological control.

More recently, sustainability concepts have been added to the IVM framework. Sustainability cannot be achieved without public, social acceptance of IVM. The newly created Right-of-Way Stewardship Council accreditation program includes sustainability requirements expressed as the following: compliance with laws, standards and BMPs; land tenure and protection of the ROW; and community stakeholder and worker relations. Stakeholder engagement and cooperation are necessary elements in sustainable IVM and the Right-of-Way Stewardship Council program.

Broad Meadow Brook

The ROW within the Broad Meadow Brook Wildlife Sanctuary had been managed using selective herbicide techniques for two decades prior to when Mass Audubon and NEP began their partnership. The well-established low-growing plant community was providing habitat for early successional wildlife species, including birds and butterflies.

Clearly, Mass Audubon is a stakeholder in how NEP manages vegetation within this ROW. As an influential environmental NGO, Mass Audubon’s role extends beyond Broad Meadow Brook. Review of the Broad Meadow management plan reveals a long list of land management goals for the sanctuary. NEP’s ROW vegetation management goals are not inconsistent with the Broad Meadow management plan. There are two specific goals related to the ROW:

- Maintain the shrub and open meadow habitat on the ROW

- Maintain the butterfly meadows within the ROW.

Maintenance of butterfly meadows required vegetation management methods beyond NEP’s typical IVM approach. Several small areas are periodically mowed by NEP to maintain the herbaceous butterfly meadows. The goal of mowing is to encourage germination of butterfly host native perennials that thrive in disturbed settings. Specifically, flat-topped white aster and common milkweed thrive in areas disturbed by mowing.

Butterfly populations have been monitored at Broad Meadow Brook since 2006. Over the period of 2006 to 2011, five consistent field sites were monitored using the same methodology. One of the sites is located on the power line ROW. In total, 78 species have been recorded at these sites. Of the total observations of butterflies recorded on the five sites, 47% occurred on the ROW site. The total species count at Broad Meadow Brook is the highest at any of the Mass Audubon’s 50-plus sanctuaries.

The habitat encouraged by IVM-based selective application of herbicides also leads to the establishment of shrub, grass and forbe species typical of early successional habitat. Birds that require this habitat thrive within the ROW. Birds found on the ROW include swamp sparrow, field sparrow, tree swallow, eastern bluebird, prairie warbler, blue-winged warbler, catbird, yellow throat, eastern towhee, indigo bunting, wild turkey and scarlet tanager. Many of these species are only observed in early successional habitats. IVM-maintained ROWs comprise a significant portion of the maintained early successional habitat in the Northeast.

The conservation value of electric ROWs for many wildlife species has been documented by many researchers for more than six decades. These values can be realized only if an integrated approach is applied and stakeholder interests are taken in to account.

Demonstration and Outreach

In 2006, NEP and Mass Audubon constructed interpretive kiosks to describe principles of IVM and the habitat and wildlife present in the power line corridor. The kiosks describe IVM and show the habitats created. Photographs of the bird and butterfly species that use the ROW habitat are shown. The partnership provides a great opportunity to showcase IVM to the thousands of visitors to the Broad Meadow Brook Sanctuary and the public that walk the trails within the sanctuary.

Broad acceptance of IVM by state regulators and environmental NGOs in the Northeast allows utility vegetation management programs to continue using herbicides as one method of vegetation control. Greater industry support for these types of partnerships will facilitate acceptance of IVM nationally.

National Grid supports this effort, in part, because of the ISO 14001 accreditation of its environmental management system. In the context of ISO 14001, this type of partnership and outreach becomes an integral part of the vegetation manager’s job. National Grid also has a demonstration site in Albany, New York, used to demonstrate IVM to regulators and stakeholders, including attendees of the 8th Symposium on Environmental Concerns in Rights-of-Way Management held in Saratoga, New York, in 2004. The industry needs more IVM partnerships with groups like the Mass Audubon and demonstration areas across the country because they go a long way toward getting a positive message out to the public that the proper use of herbicides can have many benefits to the community.

Martha Gach ([email protected]) is conservation coordinator at Massachusetts Audubon Society’s Broad Meadow Brook Conservation Center and Wildlife Sanctuary. She has 15 years of conservation experience with Mass Audubon. Gach holds a Ph.D. in ecology and evolutionary biology from the University of Michigan and a bachelor’s degree in biology from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. She also is a certified pesticide applicator in Massachusetts and a member of her local conservation commission.

Mariclaire Rigby ([email protected]) is lead vegetation strategy specialist at National Grid. She has 15 years of forestry experience, eight of which have been in transmission vegetation management with National Grid. Rigby has a bachelor’s degree in natural resource management-forestry from the State University of New York. She is an ISA Certified Arborist.

Thomas E. Sullivan ([email protected]) is senior consultant at Energy Initiatives Group, a Northeast-based energy infrastructure consulting firm. Sullivan has more than 35 years of electric utility experience as an employee and consultant to National Grid and its predecessor companies. He holds a master’s degree in biology from Boston University and a bachelor’s degree from the College of Environmental Science and Forestry at Syracuse. He is an ISA Certified Arborist and Massachusetts Licensed Forester. Sullivan is active in professional organizations. He received the Utility Arborist Award from the Utility Arborist Association in 2004.