Fifty-five years ago, linemen constructed a 69-kV distribution line on the property of a coal-fired plant in southern Illinois. Recently, Ameren Illinois had to return to the site to replace aging poles, but one major obstacle stood in the way — a fly ash pond.

While no ash had been added to the receptacle for more than 25 years, it was filled to the point where the space between the surface and the energized conductors marginally met the minimum National Electric Safety Code requirements. Plus, evolving environmental standards could require power plant operations to add more clay soil as a cap, therefore compromising the space between the ground surface and energized conductors.

Although engineering projects for pole replacements are typically routine for Michael Whittington, an engineer for Ameren Illinois, he faced spacing or distance constraints from above, below and beyond the site. Plus, a new low-voltage customer needed to be connected to the line, and an existing industrial customer served at 69 kV stood to lose hundreds of thousands of dollars if power was interrupted.

As a result, he faced unexpected structural obstacles from every conceivable angle, along with challenges in work scheduling and maintaining service.

“At every phase of the project and with design issues, there was a discovery mode where I found myself saying, ‘Oh, my. I didn’t realize that,’” Whittington says. “During 29 years sitting in this position, you see quite a bit. But this project was a rooster of its own magnitude.”

Considering Possible Solutions

Upon inspection, Ameren Illinois learned that the old H-frame structures had been filled around with fly ash to depths between 8 ft and 22 ft. When drilling new pole holes, it was essential to maintain the integrity of the fly ash pond. As such, Whittington hired a company to conduct subsurface exploration and take soil samples. If the pond’s clay liner was damaged by drilling, it could create an environmental problem as rain water could flow downward and carry contaminates into the water table.

Ameren Illinois considered raising conductors or adding low-voltage conductors to the existing pole line. However, these solutions were not plausible because of inadequate ground clearance and minimal clearances from high-voltage lines crossing over the top on the existing H structure line. The proposed relocated line had to cross under or negotiate around six medium- and high-voltage lines.

In addition, power interruption needed to be minimized because one line fed a large industrial customer with a construction plant that only shut down a few times each year. Unscheduled power interruptions could cost the customer as much as $400,000 per event. While Ameren Illinois could take advantage of an approaching three-day plant shut down, Whittington was still attempting to solve the project’s challenges and move forward with multiple tasks when the shutdown was scheduled.

“Each aspect of this was like peeling back the layers of an onion,” Whittington says. “You would overcome one obstacle and then, boom, you’d find another one. Then you had to find out more about that issue and how you could negotiate that. Nothing presented itself in one package. It was an accumulation of trial and error attempts. I was under the gun.”

Creating a Model

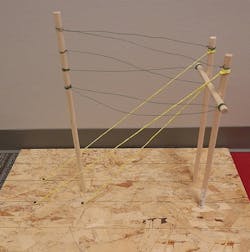

Without existing construction standards to meet the challenges, Whittington resorted to one of his strengths: ingenuity. A homemade model of twine, Christmas wreath wire and dowel rods helped the Ameren team meet the design challenges.

Whittington purchased dowel rods for the poles, borrowed Christmas wreath wire from his wife for the conducting wires and used yellow twine for the guy wires. Based on this model, the utility was able to pioneer the use of composite poles to build an H structure without guy wires backing the static conductors at the top.

“What I was really doing was just trying to see what the clearance was going to be,” Whittington says. “I wanted to have a physical structure and then run the wreath wire like the conductors would run and see how close the wreath wire came to the down guys, which were the yellow twine. That’s where the clearance got compromised.”

The model proved the guy wires backing an H structure from the static position would encroach on space required by conductors near the outer end of the spar arm. Ameren Illinois had used composite poles for line-hardening designs where the partial or full guy wires weren’t possible. However, a composite H structure with a partial guy design had not been used anywhere in Ameren. Guy wires could be established below the 69-kV spar arms on the poles.

Whittington created another model where the top 8 ft of an H pole would be free of guy wires yet have full tension on it. He asked other engineering peers for a critique of his solution and worked with Ameren Standards to design a composite pole that had a beam within the pole for adding structural strength for the unguyed area of the upper pole.

The new H structure would be built with composite dead-end spar arms and composite braces. Ameren Illinois selected composite material so all components would reach the end of their engineered life span simultaneously, as opposed to the varying life spans of wood components. The prototype model — constructed of dowel rods at Whittington’s house — was taken to the site to show construction crews what the final product would look like.

“The model was a tremendous asset for getting them into the mode to know what to build,” Whittington says.

Installing the New Structure

The final challenge was taking advantage of the three-day period when service could be stopped for the industrial customer. Since all of the construction work could not be completed before the power shutdown, crews installed and later removed a temporary 69-kV pole frame.

The linemen also used live-line construction techniques to get the new line energized and placed into service.

“The real crux of the matter was finding the solution where you could have the tops of the new H structure unguyed because of the clearance conflict and do it in a small footprint,” Whittington says. “That’s something that’s never been done in Ameren or other utilities, according to Ameren composite pole supplier.”

What started as a simple pole replacement became a highly complex and demanding project. Innovation, creativity, teamwork, communication, and a model made of dowel rods and Christmas wreath wire solved what seemed to be a never-ending puzzle.

“I used the tools I was familiar with and it worked,” Whittington says. “In the end, it was a significant expenditure, but it was the right thing to do. We came up with a product that met the requirements. We provided new service to a distribution customer and maintained service to an existing industrial customer that was in very tight circumstances. It looks good and is fully functional.

“You look at it and don’t see all of those obstacles now,” Whittington says.

Joe Mueller is a writer for Ameren Illinois.