This is not a typical story about how a new technology has improved reliability. This story is about how one utility is using strategic planning processes, quality improvement methods and other management tools to improve reliability dramatically.

Blue Ridge Electric Membership Corp. is a member-owned electric cooperative nestled in the mountains of northwest North Carolina, U.S., where it serves more than 74,000 members. The service area includes some of the highest and most rugged terrain in the Appalachian Mountains. Winds routinely exceed 50 mph (80 kmph) on cold winter nights with frequent ice and snow. These conditions make achieving outstanding electric service reliability a challenge.

Like most utilities, Blue Ridge Electric uses the IEEE Guide for Electric Power Distribution Reliability Indices to measure its electric service reliability. In the early 2000s, Blue Ridge Electric’s system average interruption duration index (SAIDI) was averaging more than 180 minutes per year, excluding major storms. Management knew that to improve member satisfaction, electric service reliability must be improved. Work began immediately on maintenance practices, operational procedures and equipment upgrades to impact reliability. By 2014, the utility had reduced its SAIDI value to 66 minutes.

Execution Premium Process

One of the tools Blue Ridge Electric employed is a strategic planning and execution process developed by The Palladium Group of Boston, Massachusetts, U.S., called the Execution Premium Process. Blue Ridge Electric has used this process for many years and, in 2012, it was the first electric cooperative inducted into Palladium’s Hall of Fame for companies that have achieved breakthrough results using strategic planning concepts.

This structured planning process guides management to focus on issues most important to the success of the company. Of course, strategy without an effective execution plan is meaningless.

The Palladium Group’s process successfully ties the strategic plan to all facets of operations so engineering, operations, accounting, member services and human resources are aligned on achieving key strategic initiatives. These initiatives are specific, measurable actions assigned to an initiative owner for accountability. Quarterly management reviews ensure the initiatives remain on schedule or are adjusted as conditions warrant.

Kaizen Tools

The second concept Blue Ridge Electric embraced isKaizen, a continuous improvement process that originated in the total quality management philosophy. Salient points of Kaizen include the following:

- Good processes equal good results

- Find the problem’s root cause

- Understand current situation

- Always speak with data and manage with facts

- Continuously plan, do, check and act on processes.

The basic Kaizen tools employed by Blue Ridge Electric in its quest to improve reliability included flowcharts, Ishikawa diagrams and

Pareto charts.

Where to Start

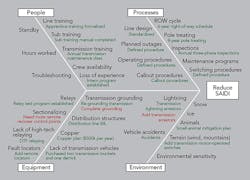

The reliability improvement process began with an Ishikawa diagram listing potential causes of poor reliability using four main categories: people, processes, equipment and environment. Using historical data, the co-op relentlessly evaluated each of these areas to determine impacts on reliability.

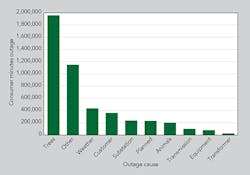

Once the likely suspects of outage causes were identified, the co-op used a Pareto chart to analyze the impact each outage cause had on reliability. Not surprisingly, tree contacts were the most common cause of outages Blue Ridge Electric identified in its analysis.

Using this data, the utility embarked on an aggressive campaign to improve its right-of-way reclearing program. The right-of-way program was redesigned around a six-year reclearing cycle with a mid-cycle reclearing of hot spots and heavily forested residential subdivisions where full clearing is not possible. In addition, the utility has an herbicide program that is also on a six-year cycle.

The Approach

Blue Ridge Electric preplans right-of-way sections to be recleared with the members in those areas and attempts to resolve any potential problems before crews begin work. To further enhance customer relations, an automated phone message is sent to members before work begins and postcards are mailed to those who could not receive the phone call.

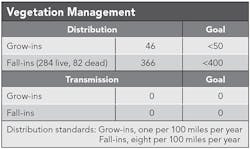

To help manage the right-of-way progress, standards were developed for tree contacts, including the number of grow-ins and fall-ins that are considered acceptable. The right-of-way standards allow no more than one grow-in per 100 miles (161 km) of line and no more than eight fall-ins per 100 miles of line on the distribution system.

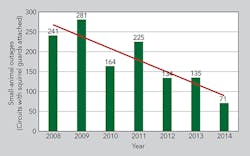

After identifying right-of-way issues, outage causes rapidly dispersed into a multitude of small issues. One problem area identified through the Pareto analysis was an excessive number of outages caused by small animals, primarily squirrels. Using multiyear outage data, Blue Ridge Electric determined which substations and circuits experienced the largest number of small-animal outages, and it began an extensive campaign to install small-animal guards on both the substation equipment and the three-phase circuits. The results of this project were dramatic with an almost two-thirds reduction in small-animal outages on the protected circuits.

An unusual issue discovered during the Kaizen analysis was what appeared to be an excessive number of planned outages occurring each month. An investigation revealed that more than 33% of the utility’s planned outages were the result of crews taking lines out of service to perform dead-line maintenance. Crews were taking lines out because contractors were being paid on a unit basis and could work faster on de-energized lines. A quick operational policy change requiring contractors to get prior approval from the utility’s area supervisor before taking a line out of service immediately reduced the number of planned outages by two-thirds.

Further Analysis

In what may be considered a bit of Monday-morning quarterbacking, Blue Ridge Electric’s director of operations began meeting with management each month to analyze an exception report listing every outage exceeding 3 hours during the previous month. As expected, most outages longer than 3 hours had logical causes such as underground cable failures or broken poles. The report also occasionally helped to identify a training need. Regular evaluation of the monthly report aided management in determining whether an outage delay was caused by equipment problems, staffing issues or the need for additional training to produce better results.

An example of this is a recent outage that lasted 4.2 hours. The co-op determined the outage restoration took longer than necessary because the crew failed to realize the problem was a defective recloser instead of a line fault. After numerous attempts to find the line fault, the crew finally tested the recloser and found the problem. Follow-up discussions with crew personnel led to a procedure of testing the protective device after the first patrol if no apparent cause is found.

As a result of monitoring the exception report, other operational protocols were implemented to reduce the number of outages and speed up restoration times. For instance, for high SAIDI events such as a substation or circuit outage, all crew pages are sent to all line personnel in the affected service district to ensure a prompt response. Another protocol resulting from the exception report is that the system dispatcher must never to leave an outage ticket unassigned for more than 30 minutes before calling in another crew. In the past, it was not unusual to hold a new outage ticket while the on-call crew finished the current outage, even if repairs on the first outage took several hours.

Maintenance and Testing

Stricter attention to regular maintenance and testing schedules for optimal operation was also identified as an opportunity to improve reliability. The co-op previously had a variable schedule of testing relays and breakers. Now the director of engineering maintains a detailed Excel spreadsheet listing every relay with dates of when it was last tested, the next test date and links to the actual test reports. At any time, the director can produce the current status of any device.

Because of the extensive use of completely self-protected transformers and minimal use of tap fuses, Blue Ridge Electric also noted an excessive number of circuit outages. The circuit outage rate, as a percentage of total number of circuits, was more than 50%. The utility set a goal to reduce the circuit outage rate to less than 30%. In addition to right-of-way improvements and small-animal guards, the cooperative began fusing all taps on the main line and fusing completely self-protected transformers. As a result, the circuit outage rate dropped to 22% by 2014.

Technology has also played a role in reliability improvement. A key example at Blue Ridge Electric is the use of remotely controlled down-line reclosers. System operators are now able to open a device approximately halfway down a line remotely to restore power to circuits while leaving only the smaller affected area out of service. This enables linemen to focus on specific repair areas, which is especially helpful for faster restoration in difficult mountainous terrain.

The Transmission System

Lastly, a somewhat distinct area for a distribution cooperative to address is its transmission system. Because of its remote service area, Blue Ridge Electric owns 280 miles (451 km) of transmission consisting of 230-kV, 100-kV and 46-kV systems. The co-op set a goal of no more than three momentary operations per 100 miles of line, or approximately nine momentary outages per year. At the time the goal was set, momentary outages averaged 15 per year. To reduce this number, all transmission line grounds were tested and corrected to 25 ohms or less, and lightning arresters were installed on the worst offending lines for momentary outages. By 2014, there were only six momentary outages.

The Very Best

As a member-owned utility, Blue Ridge Electric’s vision is to provide “nothing less than our very best” for members. This means the quest for better electric service reliability never ends, and the utility’s reliability goal is now 60 minutes of SAIDI.

Lee Layton ([email protected]) is the COO for Blue Ridge Electric Membership Corp. located in Lenoir, North Carolina, U.S. He has a BSEE degree from Auburn University and a MBA degree. Layton is a registered professional engineer in North Carolina and Georgia, and has more than 35 years of electric utility experience. He is a senior member of the IEEE and served on the Electric Power Research Institute’s electric system division advisory committee.