Montana Utility Manages Raven Roosts on Towers

Parallel single-circuit 500-kV transmission lines in central Montana — jointly owned by NorthWestern Energy, Puget Sound Energy, Portland General Electric, Avista Corp. and PacificCorp — are an integral part of the Northwest power grid. These lines have experienced numerous zero-sequence, single-phase line-to-ground (S-L-G) faults of unknown origin since being energized in 1984. Research conducted along the lines from 2002 to 2010 determined many faults were likely caused by raptor streamers. Streamers are fluid feces forcefully ejected by raptors spanning many feet in length that are conductive and can bridge the air gap between conductors and towers.

More recent S-L-G faults on the 500-kV transmission lines from January 2017 to March 2017 differed from past events because they were sustained — relay reclose unsuccessful — and, therefore, of much greater concern and consequence to the service and stability of the grid. Additionally, on three occasions in 2017, both parallel lines faulted simultaneously. Initially, the faults were identified through the energy management system (EMS) by supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) processes. Further information obtained from NorthWestern Energy’s grid operations enabled the identification of the specific towers where the faults occurred. When crews visited the towers to investigate the sustained faults of unknown origin, they found insulators heavily contaminated with bird droppings.

Initial Strategies

NorthWestern Energy’s attempts to reduce faults from the accumulation of bird droppings over the last few years have involved several strategies.

First, tower crews cleaned contaminated insulators discovered during ground inspections following faults (that is, retroactive cleaning) and during routine transmission line maintenance flights (that is, preemptive cleaning). Depending on site accessibility, crews accessed towers by either climbing or using a bucket truck and cleaned insulators by hand or with a power washer, respectively. Crews could clean a maximum of only one tower per day when climbing and cleaning with hand brushes and two towers to three towers per day when using a bucket truck and pneumatic power sprayer. The sprayer was loaded with either pulverized corn cobs or walnut shells, media that effectively removed droppings without damaging the glass insulators. In late winter 2020, a helicopter-mounted, high-pressure water sprayer enabled crews to clean eight towers per day.

Identifying The Source

Curiously, the accumulation of bird droppings and number of non-streamer faults decreased during the summer of 2017, so the identity of the avian perpetrators remained unknown until late fall. In November 2017, while Northwestern Energy crews were finishing insulator washing late one afternoon as the sun began to set, hundreds of common ravens arrived from all directions to roost on towers for the evening. Finally, the utility had identified the birds responsible for causing the recent faults.

The size of the roosts on the 500-kV lines varied and consisted of two towers to 10 towers, depending on the location. Over the years, NorthWestern Energy has found seven large roosts on its transmission lines, spanning 110 miles (177 km) in central Montana.

A Third Strategy

After determining roosting ravens were the source of the problem, NorthWestern Energy’s third strategy was to install stainless-steel, avian perch deterrents to the lattice above insulators on towers within roosts. Spikes were approximately 6 inches (152 mm) in length and ordered in coiled strips of 100 ft (30 m). Spike strips were attached with screws to various-diameter polyvinyl chloride conduits, custom cut to fit tower members of differing sizes and configurations. Crews used metal zip ties to attach conduits to towers. From June 2018 to October 2019, crews installed deterrents on an average of four towers per day. To date, they have installed deterrents on 99 towers.

Why Ravens Now?

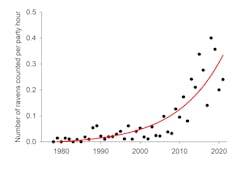

The 500-kV transmission lines have been in service for 40 years, so why did ravens only recently begin flocking to the towers for nocturnal roosting? Long-term data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) show common raven abundance in central Montana during summer has significantly increased the last 10 years to 15 years. A combination of ecological factors at the landscape scale has likely facilitated raven population growth. For example, ravens are generalist feeders and readily exploit human-provided food subsidies such as cereal grains, landfill garbage and vehicle-killed deer, all of which have increased as native habitats have been converted by varying land uses.

Strategies To Avoid

Over the years, NorthWestern Energy has considered but ultimately decided against hazing and shooting to reduce the size of raven roosts because these methods can illicit strong negative reactions from the public. More importantly, these methods have the additional potential drawback of dispersing ravens from established roosts to other towers, thereby spreading the risk of contamination and increasing the possibility for faults over a wider area.

The utility has found success with its three-pronged approach of washing insulators, installing perch deterrents and replacing glass with silicon-coated insulators.

James S. Lueck ([email protected]) has worked for NorthWestern Energy within the electric transmission department since 1975. He is currently the advisor for the 500-kV electric transmission operations. He holds an associate degree in electrical engineering technology.

Marco Restani ([email protected]) is a wildlife biologist for NorthWestern Energy. He is also professor emeritus at St. Cloud State University. His research and management program focuses on raptors and ravens. He holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Montana, master’s degree from Montana State University, and a Ph.D. degree from Utah State University.

Editor’s note: More information about NorthWestern Energy’s efforts to reduce faults caused by raven roosts can be found in a peer-reviewed, scientific paper published in the journal Human-Wildlife Interactions (Restani and Lueck 2020, 14:451–460, https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/hwi/vol14/iss3/15/).

About the Author

Marco Restani

Marco Restani ([email protected]) is a wildlife biologist for NorthWestern Energy. He is also professor emeritus at St. Cloud State University. His research and management program focuses on raptors and ravens. He holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Montana, master’s degree from Montana State University, and a Ph.D. degree from Utah State University.

James S. Lueck

James S. Lueck ([email protected]) has worked for NorthWestern Energy within the electric transmission department since 1975. He is currently the advisor for the 500-kV electric transmission operations. He holds an associate degree in electrical engineering technology.